Return to Midnight Junction in Fort Stanton Cave

10 miles and 12 hours from the surface of the Earth, a spectacular and unique cave branches out into many unexplored, inviting passages.

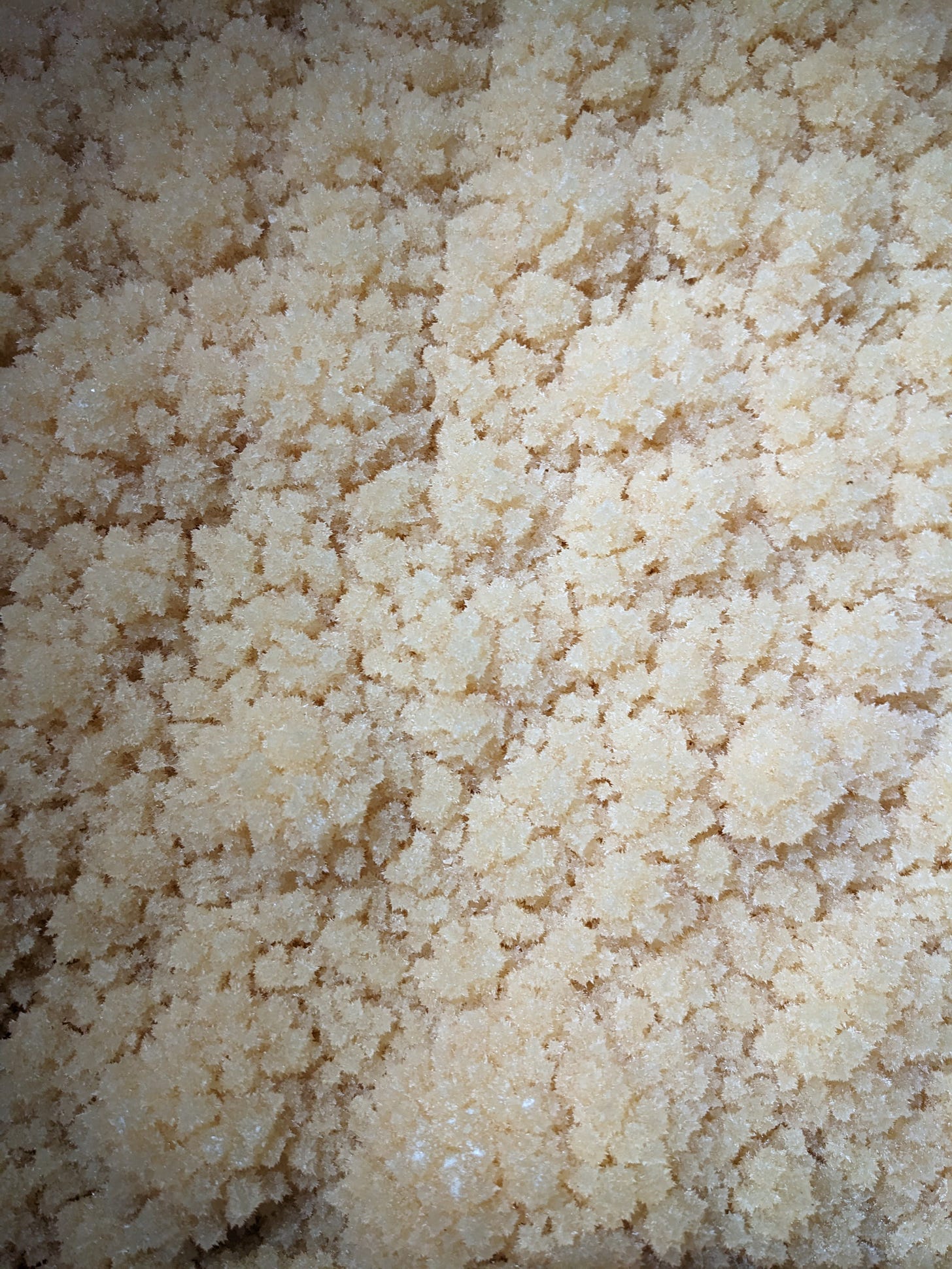

Fort Stanton Cave, just west of Roswell, New Mexico, is one of the most special caves I have ever been in. Even the historic section of the cave, which has been known to humans for centuries, is a great cave, with several miles of huge branching boreholes. In 2001, cavers who were digging and following airflow broke into a new passage that went further and was more exotic than they ever could have dreamed of. This passage, the Snowy River passage, was named for the white crystalline coating covering its floor. The Snowy River passage kept going this way for thousands of feet, then miles, and now it still goes even 13 miles from the entrance!

The current known end of Snowy River is one of the most remote points you can get to in any cave in the world, in terms of travel distance from the nearest entrance. 13 miles of underground travel from daylight is a long way to go underground. And it’s still going! Not only the Snowy River passage, but many equally outstanding side passages branch off Snowy near the far end of the cave and go off in all sorts of directions underneath the Sierra Blanca mountains. Leads (unexplored passages where no human has ever set foot or has any idea what is there) abound in the far reaches of the cave. Exploration trips out to the remote parts of Snowy River and beyond are fantastic adventures, but they are also very serious. There’s no communication with the outside world when you’re underground, as cell service and all other feasible forms of wireless communication can’t penetrate the bedrock. When you’re that far from any vestiges of human civilization, you must take your actions seriously and be extremely deliberate and cautious with your every move. If anything goes wrong while you’re in the more remote areas of the cave, you’ll have to send part of your team out 10+ miles and 12+ hours of travel to the surface, where they will have to recruit more people to repeat the same journey to help you. Expect to be on your own for at least a full day, if not more, before any help can arrive.

The sense of extreme isolation and remoteness you get in the outermost limits of a cave like Fort Stanton can feel crushing and intense, yet also invigorating; it certainly draws me to caving. Fort Stanton trips are also special because the cave has excellent leads, due to both the remote nature of the cave and difficulty of getting out there, and the tightly controlled access to the cave from the Bureau of Land Management. I can think of few caves with so many walking-sized leads going off the map into the unknown.

This past June, James Hunter invited me on an exploration trip he was leading to the Midnight Junction area. At Midnight Junction there’s an established camp, a little over 10 miles of travel from the entrance. It was named because it was discovered at midnight, on a long day trip, before anyone was camping in the cave. After finding that intersection at midnight after a long day, they still had 10+ miles to travel to get back out of the cave! That was the last day trip anyone did that far in the cave; now anyone exploring the far reaches of the cave camps at Midnight Junction or bivvies beyond there, closer to where they’re exploring.

Midnight Junction is an ideal location for a camp, because that’s where the cave changes character from pretty much just one passage going forever in one direction (Snowy River) to a maze of passages branching out in all different directions. At Midnight Junction, one passage branches left off Snowy River. A few minutes of travel later, you get to a T intersection, Harmony Hall, where passages go both left and right. Both of those branches have many different passages branching off them, including many unexplored leads.

I had been on one exploration camp trip to the Midnight Junction area before. It was one of the most incredible caving trips I had ever done, and I was eagerly awaiting returning to this area. There is plenty more exploration to be done in the Midnight Junction area, as the maze is nowhere near having given up all its secrets.

This trip would be a four day camp trip: one day to travel to the Midnight Junction camp, two days to survey new passages, then one day to travel out to the surface. We would enter the cave Thursday June 26, and exit Sunday June 29. The four of us on the trip, James Hunter, Beth Cortright, Ben Tobin, and myself, all met at the Fort Stanton bunkhouse on Wednesday evening. There we packed our bags, discussed the plan and timeline for the trip one last time (after many such discussions in the days and weeks prior), and went to bed early in preparation for our long day the next day.

Thursday, June 26

We got up bright and early at 6am, early enough to leave the bunkhouse at 7:30am and get in the cave at 8am. The first hour of caving brings you through the historic section of the cave, which is mostly huge mud-filled borehole. There is a short crawl into Don Sawyer Memorial Hall, where a dig shaft supported with stainless steel ladders and supports descends straight down into the bedrock. That’s the site of the second dig shaft that cavers used to break into Snowy River. They first accessed Snowy via a breakdown dig called Priority Seven. They explored Snowy for many years via Priority Seven, but the dangerous, unstable breakdown in that dig eventually led them to find a new way in, by digging in Don Sawyer Memorial Hall.

At the bottom of the dig shaft is the Mud Turtle Passage, a 15 minute hands-and-knees crawl. The crawl ends at Turtle Junction, where a plastic tarp lets you change into your clean Snowy River clothes before stepping onto the formation. The Snowy River formation is a clean, pearly white standout in the middle of a cave full of mud, and we go to great lengths not to get Snowy dirty to maintain its pristine appearance. Changing clothes when switching between dirty mode caving and caving on Snowy is one way we keep it clean.

After a few minutes of walking down gorgeous Snowy passage, we arrive at another course of action required to keep Snowy clean: a shoe cover crossing. At Independence Hall, Snowy River ducks under a low ceiling, and we step off the formation onto the dirt banks on the side, to walk where the passage is large instead of crawling on Snowy underneath a low ceiling. To keep our shoes clean, we put on shoe covers for this short dirty section. Putting on and taking off shoe covers at spots like this is a somewhat delicate maneuver. When putting shoe covers on, you have to stand on one leg, put a shoe cover on the other foot, while sticking your leg out over the dirt section so as not to spill dirt from your shoe covers on Snowy, step down onto the dirty section, and do the same for the other foot. All while standing on a potentially uneven surface, and while carrying a 40+ pound pack. Very balancey.

In some spots where you have to step off Snowy, there are plastic tarps we call “magic carpets” that let you walk off snowy while keeping your shoes clean. There are several hundred of these on the way out to Midnight Junction, and they make the trip out much easier, as it takes much less time and effort to use them than it does to do the shoe cover dance.

It’s not just your feet that need to avoid touching dirt. The walls and ceiling of the Snowy River Passage are usually covered in dirt, and the slightest nudge on them will knock off dark brown debris onto the formation. This is not a problem when Snowy is in the center of a large walking borehole, as in the first picture, but it presents a challenge when Snowy weaves its way to the edges of the passage and passes under roofs and other obstacles. There you play a strange game of “The walls, ceiling, and some of the floor are lava”, like the childhood game “The floor is lava” but much stranger and more interesting.

The trip out to Midnight Junction is a little over 10 miles of travel underground. Much of that distance is easy, glorious walking on Snowy. However, there is a lot of less glamorous travel ranging anywhere from slightly hunched over stoopwalking, to low belly crawling, to perilous weaving around dirty obstacles while trying not to touch anything and get Snowy dirty. And that’s just on Snowy. In several sections you get off Snowy, either because it’s covered in breakdown (talus rocks) you have to scramble over, or the route on Snowy is so small and difficult that the standard route is via side passages. When you’re off Snowy, you’re often doing exposed breakdown scrambling above cliffs, or maneuvering around obstacles in small passage that feels more like normal caving. Depending on the length and character of the parts of the route that go off Snowy, you either change into full dirty mode (at the Black Rock Bypass, an hour long route through small, moderately strenuous passage that bypasses the worst crawls on Snowy), or just change your shoes and kneepads (at Rough Country, a long section of breakdown borehole that is huge but exposed and requires some scrambling), or just put on shoe covers (in many places, but in particular at a long section between Rough Country and the Midnight Junction camp). Doing a less-than-full outfit change saves time and inconvenience, but it makes the travel in that section more involved, as you have to ensure that your clean clothes and pack don’t get dirty. Breakdown scrambling in shoe covers can feel particularly high-stakes, as the shoe covers are slippery and your feet love to slide around in them.

We did have one task assigned to us for our trip out to Midnight Junction. There were two large first aid kits stashed at Higher Hopes (a little over six hours in, just past Mount Airy and the Eggshell Trail). We were to pick up both of them and transport one to Finger Lakes and one to Midnight Junction. I was able to fit a whole kit in my pack after giving someone else an empty water bottle of mine to make space. We didn’t have to unpack them and stuff the components in various nooks and crannies, as we thought we would.

I won’t write too much more about the trip to Midnight Junction, as I summarized that leg of the trek in my post about my last Fort Stanton trip. The trip in felt similar to the previous time, but just a bit easier, as it often does the second time around. I definitely did better with my water consumption. When I got to Finger Lakes, the first water source on the trip, eight miles and about eight hours into the cave, I had only drunk 1.2 L of water. Reducing how much water you drink is very useful, as you have to carry all your pee out of the cave. Four days of piss is a lot to carry! I made sure to only drink water after I had cooled down a few minutes after stopping. I find that this tactic greatly reduces my water consumption; I used it to great effect in Lechuguilla a few weeks ago.

We got to Midnight Junction at 7:40pm, in a little under 12 hours. That was slightly faster than the time from my previous trip, 13 hours. I felt great on the way in. I changed up my clothing and shoes a little bit from last time and was pretty happy with those choices. I wore lightweight, thin-soled, zero drop barefoot-style shoes for both my clean mode and dirty mode shoes, instead of the Walmart slip-ons that are a popular choice for Snowy shoes and that I wore last time. The barefoot-style shoes aren’t much lighter, but they do save a lot of pack space, as the Walmart shoes have thick foam soles. I even took the insoles out of my clean mode shoes to save a little pack space. That was honestly an excellent idea if only because it let me feel the fine-grained texture of Snowy through the thin, flexible soles of my shoes as I walked on it. It was wonderful to be reminded with every step that I was walking on an incredible cave formation; walking on a cloud. Snowy has just enough features to make walking on it with little sole perceptually interesting, but not so many features that it hurts your feet. I didn’t get sick of it even after 15+ miles of walking on Snowy over the course of the trip.

I also wore shorts in clean mode. That helped with both pack space and heat management. I definitely got less hot, and thus drank less water, and thus peed less, while wearing shorts. The cave is 55 degrees, and not incredibly humid like most caves are, but I still get hot when moving fast there while wearing long pants. I also wore a short-sleeve shirt in dirty mode, with elbow pads. That probably resulted in net more pack volume (elbow pads take up lots of space), but it helped with heat management, which is much more critical in dirty mode, so it was worth it. With elbow pads, I didn’t have any trouble keeping my arms sufficiently clean for travel on Snowy. My clean and dirty mode shirts were both Hawaiian shirts, and my clean mode shorts were Hawaiian patterned, fitting with a style I’ve been into lately. And fitting with a mood I think is appropriate for any Fort Stanton trip: party time! We get to go in one of the most incredible caves in the world, better dress for the special occasion!

The Midnight Junction camp is, in contrast to the rest of the cave, just OK. Not the best cave camp I’ve stayed in, but not the worst. Maybe second worst? Stay tuned for the upcoming Tears of the Turtle trip report part two to hear about that…

It’s a series of four tarps laid down in a line on a dirt bank on the side of Snowy River. Each tarp is your living space for the next three nights. They’re fairly small, about 5 ft by 12 ft. You want to keep most or all of your stuff on the tarp, as it’s the only clean surface in the sea of dirt, and you’ll need to keep the inside of your camp pack clean for the trip back down Snowy. So anything that isn’t exposed to the cave for dirty-mode caving stays there, leaving you with just enough room to sleep. When you’re on the tarp, you have to be in clean mode, to keep the tarp and all your stuff on it clean. So you can’t go wandering aimlessly around the camp area, sitting down on things or hanging out next to your friends while also conveniently accessing your stuff. You can get off your tarp of course, but you have to put on shoe covers to do so, and if you want to sit down on anything you need to be in dirty mode, which means you can’t get on your tarp. I call this configuration “tarp jail”. Again, it’s not the worst cave camp in the world, because it’s warm, dry, has pre-stashed sleeping bags and pads and stoves and such, has enough space to stand up fully, has a good water source, and has enough space to be able to go take a dump with privacy, without all your friends watching you. All luxuries that are not available in some of the cave camps I’ve camped at!

We collected water from just upstream of Harmony Hall, a two minute walk from camp. Normally there’s a flowing water at Harmony Hall, the intersection just beyond Midnight Junction, but it was dry now. John Dunham noted the low water on his Midnight Junction trip, the most recent trip there, last month. He was worried that the water might totally dry up over the next month before we got there, so he made sure to leave some water stashed at camp so we wouldn’t be totally screwed if we got to camp the water source had dried up. But it was fine when we got there; the water level seemed unchanged from what I saw in the photos from John’s last trip.

Although we had plenty of water, it did taste funny. It had a minerally taste, like tap water, but much stronger and kind of bad. The pool being stagnant instead of flowing probably contributed to the off taste. The others opted to treat their water, which people rarely do in Fort Stanton. I figured maybe I should as well, but I never got around to treating any of my water. Oh well. I’m writing this trip report two weeks later and I don’t seem to be dying of dysentery, so probably it’s fine?

Here’s a table with times and quantity of water consumed at various landmarks on the way to Midnight Junction, for my own personal reference and/or for the reference of anyone else heading out to Midnight Junction. There’s water at Finger Lakes, so I only record water consumption up to Finger Lakes.

Friday, June 27

We got up at 6:30 to James’ alarm. Ben and I, still sharing our cooking spot, immediately started making hot water for breakfast. I made a bowl of hot Dinner Mix, the same as last night and the same as every other breakfast and dinner I have eaten in the cave. I also made a small cup of coffee, about a third of my usual dose. That tiny dose was enough to make me poop that morning (a critical checklist item at cave camp!) without making me generate lots of pee that I would have to carry out.

As much as I complain about the Midnight Junction camp, I will admit that its suboptimal nature makes you not want to hang out at camp too much; it makes you want to go to sleep immediately at night, and get up and get out of camp and go caving immediately in the morning. Plush cave camps, especially in unpleasant caves (the opposite situation to Midnight Junction/Fort Stanton) can make it a little too easy to lounge around in camp, doing anything but what you came there for: to go caving and explore new passage. I was especially motivated to get out of camp and get to the leads that morning, and we were off by 8:28am. Two hours to get out of camp and start caving isn’t super fast, but it’s certainly quicker than many other times I’ve been caving.

To get to This is Ridiculous, you take the dirty passage from Midnight Junction to Harmony Hall, then turn left towards the pools where we got water. You follow that passage, Midnight Creek, for 27 stations that are a mix of crawling (including some precarious superman crawling above pools) and walking in huge passage. At MJ27, you ascend a dirt slope up and right into an upper level of the Midnight Creek passage. After a few stations this upper level branches off Midnight Creek and becomes its own separate canyon passage.

Here, where the canyon first branches off Midnight Creek, it is tight, grabby, and annoying; yet also densely decorated, beautiful, and delicate. The need to not sully the clean formations and not break the delicate stalactites and helictites makes travel through the tight snaggy canyon even more tricky. Here I understood why they named the passage This is Ridiculous: it’s quite the stark contrast to be thrashing and struggling through a narrow canyon that grabs you and all of your stuff, only to be confronted with clean velvet flowstone and other pretties that you must delicately maneuver past. As I was exerting myself in the canyon, I was continually entertained by the colorful displays of brilliant striped flowstone and dense, featured helictite forests. I didn’t take many pictures as I was focused on the task at hand, getting through this passage. I did tear my vibrant red Hawaiian shirt in this passage as it snagged on some popcorn, which was unfortunate. Oh well, I guess it’s a cave shirt now.

I did stop to take pictures at one spot of something particularly notable. I saw a fully articulated skeleton of some sort of mammal sitting on a ledge in This is Ridiculous, at MJA18. The skull was missing, but the rest of the skeleton was remarkably articulated. Gary Morgan from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science identified it as a likely ringtail, although with the skull missing it’s impossible to say for sure.

It was sitting on a ledge high above the floor, 10 ft perhaps? If it was washed in via a flood, it would be one hell of a flood to reach a ledge that high. Still, there is reason to believe it may have been a flood that brought this animal here. It was very far into the cave, over 10 miles via human-sized passage. While there may be other entrances accessible to small animals, there are several hundred feet of overburden at this spot, so any animal would still have a long travel time to get here even if there were a direct small-animal-sized conduit from the surface above. There were some small bones right at the (missing) skull. Perhaps part of this animal’s last meal?

Besides a quick stop to document that skeleton, we all powered through This is Ridiculous to the continuation of the passage that was our lead. The passage followed stations MJ27A-MJ27Z, then continued as MJA1-MJA47. After ~70 stations (not quite 74, as a few shots were splays) we arrived at MJA47 and our lead. Here the passage abruptly changed character from the tight canyon we traveled through to a comfortable keyhole, with a 10 ft diameter tube at the top and that tight canyon in the floor. Either the passage changed character, or this is the first time it made sense to get up into the top of the keyhole that may have been there the whole time. What a spot for the last team to turn around at!

We got to the lead at 9:51am. Under an hour and a half from camp. I stashed most of a liter of water at the lead, as it was clear I wouldn’t need most of the three liters I hauled in there. We got set up to survey; Ben would sketch plan and cross sections, I would sketch profile and do front sights, Beth would make stations and do back sights, and James would do inventory and take pictures (which is actually required at every station when surveying in Fort Stanton). I hadn’t sketched in Fort Stanton before. Although sketching profile doesn’t really count—it’s unlikely that anyone will ever make a profile map using the profile sketches of this horizontal cave, so the profile sketches will probably remain forever archived, never to be made into a map.

As we started surveying, we were able to continue along that comfortable 10 ft diameter tube at the top of the keyhole passage. Stemming over the gaping crack in the floor got a little exposed, but was never difficult. The dense forests of formations continued to line the walls and ceiling of the passage, providing obstacles to avoid, although it was much easier to avoid them in this large tube. Even when they got huge.

And boy, did they get huge. Our first shot brought us down that comfy 10 ft diameter keyhole tube where rich velvet flowstone poured down the floors of the tube into the canyon below, dense hanging gardens of soda straws dangled from the ceiling, and deformed, chaotic helictites grew out of the walls. After a few stations, we came across one of the more impressive clusters of gypsum needles I have ever seen, even more spectacular than those from the Porcupine Passage we found on my previous trip. This was classic Fort Stanton passage.

The tall (~20 ft) canyon in the floor added an interesting obstacle that made it feel like real caving. We had to mind the slick flowstone sloping down to the keyhole canyon while we traversed the small ledges in the tube atop the keyhole. Sometimes the canyon got quite wide and we had to do some creative stemming moves to cross from side to side. You must always be vigilant when doing exposed, high-consequence movement like that in a cave, but in virgin cave like this, where zero humans have ever come through and knocked any loose stuff off, you must be even more on guard than usual. Rock that looks solid may dislodge with the slightest touch, as nothing has been there to disturb it from its resting place for thousands of years until you come along. The delicate, pristine formations that we were trying to avoid in order to not damage them added an extra challenge to this fun, sporty canyon traverse.

I kept expecting for the keyhole to end and force us downwards, and for the passage to return to the character it started at: tight and grabby. But that never happened. The tube atop the keyhole never really ended, except for some short sections where we lost the tube but quickly regained it. In a few spots, the canyon at the bottom of the keyhole got wide enough where we could get down to the floor and walk in it, instead of stemming in the tube above it. That made this already nice passage feel extra luxurious, although we did lose the formation gardens when we dropped down to the floor.

When we dropped down to the floor, we could see that there’s a small, beige/white, Snowy-River-like formation in this floor. Not as thick nor impressive as Snowy proper, and without the distinct cauliflower texture, but it was notable nonetheless. We also eventually started seeing pools in the floor. Ben said he could see them faintly flowing, although I couldn’t tell. They just seemed like standing water to me.

Another interesting change in the character of the passage occurred at MJA79, where we climbed into an upper level that was the continuation of the keyhole tube, as the canyon branched off right and ditched the tube. In that upper level, we picked up another series of pools in the floor, although we lost the water again, as that minor canyon again branched off our upper-level tube at MJA84. Here, our tube turned dry, and we gained a pleasant soft sand floor. It was a nice change to walk on soft sand after stemming above a floorless canyon for most of the day.

At MJA87, our dry sand tube turned into a crawl. We thought that the good times might be ending, and that we would have to go back to either of the canyons that this tube lost as our leads. However, at MJA92 we regained a tall wet canyon with a Snowy-like formation in the floor, and we were back in our usual keyhole passage. The canyon we lost at MJA79, and the minor canyon we lost at MJA84, and the canyon we gained at MJA92, are all leads, although they’re not super promising, as it’s likely they’ll all connect through to MJA92. But maybe not—there’s always a chance one of them could intersect another passage or go off in another direction.

After regaining the lower canyon, the passage changed character yet again. Instead of the classic keyhole cross section with a large tube sitting atop a tall narrow canyon, we instead had a tall, wider canyon sitting atop a tall, narrower canyon. There was a clear ledge system that marked the boundary of the upper wide canyon and lower narrow canyon that we stemmed across the rest of the way. We started marking leads in the ceiling when we couldn’t get a view of the top of the upper canyon, although I don’t think any of them are good leads. They’re just little alcoves where the passage geometry doesn’t let you definitively see the whole ceiling.

The passage stayed intensely decorated after regaining the canyon in the floor. There were formations with wind-grown formations growing on them—meta-formations as I sometimes call them. This indicates that the passage had directional airflow for a long period of time in the past. That’s a good sign that this passage goes somewhere (“if it blows, it goes!”). Ben claimed he felt air, although I never felt any. The velvet flowstone also became more common, and it became impossible to avoid in spots as it plastered the whole walls where we had to stem. It was not really feasible to use shoe covers in involved stemming passage like this, so we just picked our spots to step on and concentrated our impact in those few spots. We climbed across some of the velvety areas with bare hands, to keep it clean. There I learned that velvet flowstone is full of tiny, sharp, grabby spines, like the glochids on a Prickly Pear fruit, or sharp velcro. It kind of hurt my hands, although I didn’t mind, as it was one of the rare occasions when it made sense, from an impact-minimization standpoint, to touch pristine flowstone with bare hands. Forbidden fruit vibes. As I stemmed across the velvety canyon, carefully picking spots for my feet and feeling little prickly jabs of pain on the palms of my hands as I carefully touched the forbidden fruit, I felt very in touch with the medium.

At MJA108, 60 stations and 2000 ft of survey in, we decided to call it. It was not quite 8pm then. We had done just about 10 hours of survey. I felt pretty good about my efficiency when sketching profile and doing front sights. 2000 ft in 10 hours, not bad! And it was all nice, significant passage too, trending south towards the Barefoot Boulevard area of the cave. We turned around at more of the same: 30 ft tall canyon passage, with a clear ledge system partway up allowing easy travel at the interface between narrow and wide parts of the canyon. At 5 ft wide, it was slightly narrower than the passage right before that point, but clearly continuing off into the distance. A great lead that I’m excited to return to!

We departed for camp at 8:06pm. Travel through our survey was fast and easy; it probably took no more than half an hour. Travel through the first part of This is Ridiculous felt similarly ridiculous as it did in the morning, but with some care and finesse we were back in Midnight Creek. On the way back, I took everyone through the alternate route back to camp that we discovered on my trip last year: up into the MA borehole at MJ20, left at the MA borehole, then right into our little shortcut that drops you into La Culebra at MK4. I thought this route would be longer but less effort, as it cuts off some low wet crawling in Midnight Creek around MK10-20. Plus, we got to see the massive MA borehole, which is the largest cave passage I’ve ever been in that doesn’t have a name (MA is the survey junction). However, the others thought it was more effort, as it involved hiking up some huge breakdown hills in the MA borehole. I always feel way more at home hiking up steep breakdown than crawling, so perhaps I discounted the effort required to go that route. Oh well. We made it back to camp at 9:51pm, a very reasonable time. I was in bed before 11pm.

I drank 1.25 L of water and peed 825 mL while I was out. 3 L of water was way too much to pack. I ate 3 of my cheese and pepperoni wraps, about 1/2 a cup of pepitas, and a bunch of dried mangoes. That was enough food, although it may have been nice to pack more to have more margin for error.

Saturday, June 28

We woke up at 7:15am, to an alarm that James had set to give us just over eight hours of sleep. As much as the lead we turned around at yesterday was excellent, and very much worth returning to, James wanted to go to a different part of the cave, and had different leads in mind. The leads were in the Borderlands area, MK60 and beyond. There the map was full of question marks branching out from the known passage walls. It looked as if most of them were going in a direction that would make them quickly connect with known passage, although they were worth checking out, as surely a place where the passages had such porous walls would do something interesting.

We left camp at 8:55am. The route to Borderlands turns right at Harmony Hall, instead of left up Midnight Creek as we did the day before. There we followed the La Culebra passage down 60 stations of walking down huge borehole, with only a few short ducks under boulders or other low ceilings. We got to the first leads at MK60. The first few leads starting at MK60 seemed uninteresting, almost certain to connect into known passage. At MK64, however, James had his interest piqued by a lead. It was a low crawl underneath the right (west) wall of the borehole. Although it looked pretty terrible at 1 ft tall and 30 ft wide, it’s also where the dry streambed in the passage appeared from, so it was interesting. In the borehole beyond they never again saw that (presumably not always) dry streambed, so following it could be promising. Following the water and following the air are always good strategies for cave exploration.

I will admit that I was somewhat skeptical of this lead, a 1 ft tall belly crawl underneath the wall of a borehole. But apparently they were unable to follow the lower level of the borehole much further, so this could be a promising way on. I knew that James knows this cave quite well, so I would see where it would take us.

We were at our lead at MK64 at 9:56am, just an hour out from camp. We mostly stuck to the same roles as yesterday, with a few changes. I just sketched profile instead of doing profile and front sights. Ben did plan and cross sections, although I picked up a few cross sections at the very end. Beth did front sights, James did photography (Fort Stanton is the only cave exploration project I know of that requires photographs at every station), and James and Beth split up inventory.

The passage continued as belly crawling for at least 300 ft. It was easy survey, as we got long shots in the flat pancake crawl, and there was very little detail to sketch. It kinda felt like cheating just drawing straight lines connecting the floors and ceiling on two stations 30+ ft apart, but that’s really what it was like. James was able to set stations at spots where there was enough room to sit (not stand) up, which made the survey more comfortable, as the passage was otherwise entirely belly crawl. At least we had some nice fossils in the ceiling to entertain us. For that reason, Beth named the passage the Beachcomber’s Crawl. Fitting, not only because of the marine fossils, but because of the damp sand in the floor.

Interestingly, the sand in the floor was damp, in places damp enough that when you pushed a small hole into the sand, it filled with water. I made sure to keep the survey book out of the sand, and planked hard to keep my torso out of the water. Ben announced that without a fleece, he wouldn’t last long in these conditions, temperature-wise. I had a fleece, but I certainly wouldn’t complain if our team called it and moved on to a better lead.

However, after 7 stations and 300 ft, we reached a nice standing room. A flowstone slope led up and left (kneepads off to keep it clean) into another standing room. Here we tied in to MK68, which was in the same La Culebra passage we had just departed a few stations ago at MK64. We had surveyed a small loop.

Where we returned to La Culebra at MK68, there was another lead. Probably the original team (which included James among others) left this lead because it was exquisitely clean and decorated. We donned our shoe covers, took off our gloves and carefully entered a dried-up pool basin, full of exotic formations which were all a deep, vibrant yellow.

The floor was coated in translucent yellow pointy crystals that grew like clusters of bushes out of the ground. These had a very different shape and texture than the cauliflower-like coating of Snowy River, although they nominally formed from the same process—standing water in pools slowly evaporating away and precipitating out calcite crystals. I wonder what made them so different? Little stubby pool fingers grew out of the walls just below what was an obvious old water line. Shiny yellow velvet flowstone poured down the walls at the entrance to the room, and from a too-tight hole in the ceiling, and turned into draperies as they spilled over overhangs. Long ribbons of striped, colorful cave bacon snaked their way down the sloping ceiling. If these words don’t make any sense, just look at the pictures of it all. All these are at MJA12-13:

The room was intensely decorated and beautiful, but kind of small, so there wasn’t a ton to sketch. So we took plenty of time to take pictures and document this find. The passage ends there, so it’s very possible that zero humans will ever return. Which is a little sad if you ask me!

We returned to where we tied in to La Culebra at MK68 and had a lunch break. It was about 12:30pm then. We had the option of continuing on to Borderlands to look for better leads (and there were certainly good leads there), or continuing down the low belly crawl that went southwest from ML7, instead of east into La Culebra. James decided to continue down our belly crawl. La Culebra ended in breakdown there, and the way on was via the upper level Borderlands passage, so if this low stream crawl connected to whatever existed of La Culebra on the other side of the breakdown, we would be off to the races surveying big borehole. So down the crawl we went.

Two stations and 100 ft later at ML15, the passage opened up into a nice standing room with a deep pool. It had a breakdown wall on the right (east) side that was probably the only thing nominally separating it from the continuation of La Culebra, although I couldn’t find any gaps in it. So we continued down yet another wet sandy crawl. At ML20, another 200 ft of crawling away, we were in a stand-up walking stream passage with bedrock walls all around that was clearly a distinct passage from La Culebra. There was even a lead on our right (southwest), going away from La Culebra. It’s a pretty good looking lead—you’d scramble up an easy flowstone slope (maybe bring a handline for everyone after the first person), although it’s clean enough that you’d probably want a full clothing change, or at the very least clean shoe covers and gloves. By now, we had consistent pools and/or a flowing stream in the floor, and it took a little finesse to avoid stepping or crawling in the water and getting wet.

Now we were in passage that seemed like it would be at home in Kentucky, not New Mexico: a muddy walking tube (~10-15 ft diameter) with a stream in the floor. James was right! The dry streambed he saw coming out of the wall/floor near the end of La Culebra really was a promising feature to follow.

The passage continued this way for quite a while: pleasant walking passage, with a flowing stream, mud on the floor, and some sporting moves to get across the stream when the walkway or ledge on one side ended. The passage was large enough to be pleasant, but small enough to make for easy and fast sketching. I took a few cross sections from Ben, although he did almost all of the cross sections that day.

I think this was the most flowing water I’ve ever seen in Fort Stanton, with the possible exception of a Snowy crossing in the far south (SRS770) that had tons of flowing water the previous May. Harmony Hall didn’t have this much water when I was there and it was flowing last May.

Right around the time we were starting to feel like it was time to turn back, near 6pm, the passage changed character from the familiar muddy tube with a stream. It became a keyhole, with the stream in a canyon below a ledge system we were walking on. The keyhole with the stream branched off the keyhole to the right at ML39. The keyhole turned left and continued as a dry passage full of gypsum decorations, which we hadn’t seen up to this point today. Where the stream went right and the tube went left was a high lead going straight ahead up a mud-covered flowstone slope (easy climb, but maybe bring a handline for everyone after the first person). We had reached a four-way intersection! We figured this was a good time to turn around and head back to camp. As much as it is tempting to push onwards in moments like these when the passage gets really good, those moments can also be good times to end the day and leave the remaining survey for the next trip, because the excellent lead(s) will entice you and others to return. We wrapped up the day with 40 stations and 2022 ft of survey. Pretty good for 8.5 hours of survey.

I sketched one last cross section at the dry walking lead at ML40, and we took a group photo there. After a quick snack/water/pee break, we departed for camp at 6:30pm. We left a 7 ft wide 10 ft tall dry walking lead (ML40), a 16 ft wide 12 ft tall inverted T-shaped wet stream passage with great airflow (ML39), and a 10 ft wide 5 ft tall stoopwalking lead up that short flowstone climb (ML38). I am excited to return to all of those leads! The airflow at ML38 is especially interesting. You can clearly see the flagging station ML39 blow in the wind; it’s not some phantom air that cavers always feel because they want it to be there. Although, it’s possible that the air there is just caused by flowing water moving air along with it. I’ll just have to return to see! Fort Stanton has very little airflow, since the airlock at the start of the Mud Turtle crawl seals up the air pretty good, so any passage with obvious airflow is significant and interesting. I often feel air in the Black Rock Bypass, but I didn’t feel it going in on Thursday. Besides that and the airlock when it’s open, I’ve never felt air in the cave.

The trip back was uneventful. Our surveyed passage went by surprisingly fast, probably 20 minutes. The walk back down the La Culebra borehole was as serene as ever. I ate a bunch of dates before our commute back to camp and got a sugar high, so by the time I got to La Culebra I was buzzing and ready to power walk, and James had to politely remind me that we should stick together, that I shouldn’t sprint off to camp as fast as I could. After a stop to fill up water at MJ10, we were all back at camp at 7:49pm. Not counting the water stop, it’s about an hour of travel time to get to the excellent complex of leads at ML38-40.

We spent the rest of the night packing up camp as much as we could, as we would be getting up bright and early the next day for our 12ish hours of travel back to the surface. Ben and I had work Monday morning, so we wanted to get an early start and get back to Carlsbad/Albuquerque at a reasonable hour Sunday night. I used a plastic putty knife that Beth brought to scrape all the mud off my dirty kneepads, elbow pads, and pack, to make them lighter and lower volume for the trip out. Not only was it extremely effective in getting debris off those items, it was also extremely satisfying to use. It kind of felt like doing an ASMR-esque activity like cutting up soap in this video, but without the satisfying sound, only the satisfying tactile and visual sensations. See also this pressure washing ASMR video to get a sense of the vibes. It’s like that, but a plastic putty knife instead of a power washer. Thanks Beth for bringing it! I’ll bring one next time for sure. And maybe stash it at Midnight Junction, if that’s allowed?

We decided to get up at 4:30am the next morning. That should get us out of camp by 6:30am, which would mean the surface by 6:30pm if we stuck to the same pace going in, or maybe a little later due to our tiredness from several days of caving and the extra weight we’d have from the several days of pee and poop we’d be carrying. I was in bed by 9:35pm. Early enough, I guess.

For my reference—I drank 850 mL of water and peed 750 mL while out of camp for the day.

Sunday, June 29

We woke up to James’ alarm at 4:30am and were out of camp by 6:15am, pretty fast. My pack started out pretty full, but that was with 2 pairs of elbow and knee pads stuffed in there, as you don’t need them in between Midnight Junction and Rough Country. With one pair of kneepads and elbow pads out of the pack, I knew I would have enough space for the dirty pack cover that was waiting for me at Black Rock Bypass, and the two small bottles of pee I left at Finger Lakes and Mount Airy.

The trip out was fairly uneventful. We got to the start of Rough Country at 7:49am. At first we didn’t notice, and started doing it in shoe covers. We had already been in and out of shoe covers a bunch so far, so it was easy to miss the spot where the dirty breakdown starts and doesn’t stop for a while. But I noticed a tricky climb-up that I distinctly remembered as one of the cruxes of Rough Country, and we stopped to change. Well, most of us at least. James decided to keep his clean shoes and dirty shoe covers on. I changed into dirty shoes because there is some kinda serious exposed scrambling in Rough Country, and I didn’t want to do it in shoe covers. As a reminder, James Hunter is the guy who did the entire Kansas Twister climb in Lechuguilla with about a dozen bolts, all drilled by hand. He’s hardcore!

We stopped in the middle of Rough Country to install a webbing handline at one of the sketchier exposed traverses. In this spot, you traverse across a sloping dirt ledge above a ~30 ft drop. It’s secure enough that plenty of people have done it and no one’s complained too much, but I figured a handline would still be nice to have, so I suggested we do it. We took a ~50 ft piece of webbing stashed at camp in the morning and left it at the traverse, tied to boulders on either side and tied to a rock protrusion in the middle. That should make the traverse a little more chill, but still serious, because no one will have a harness to clip into the traverse line. It’s just there to grab on to in case you want it.

We got to Finger Lakes at 8:50am. Similar time so far to the way in. I didn’t even fill up water there, as I hardly drank any of my liter that I took from Midnight Junction, and I had a liter and a half stashed at various points for the way out. Higher Hopes was our next major stop; we did a lunch break there at 11:40am. Again, about the same time as on the way in. The near side of Mount Airy, where I stashed some food and water, was closer than we remembered, and we were there at 12:28pm. I had some of my water I stashed there but didn’t eat any of the food. At 1:35pm we were all at the far side of the Black Rock Bypass. James and Beth went first, and Ben and I hung out and cooled off while they changed. When Ben and I got to the Black Rock Bypass, I noticed that it was distinctly windy. It did not have this air on the way in! But I do remember it having air like that on a prior trip. At 2:45pm, we were all on the near side of Black Rock Bypass. We powered through the last crawling section of Snowy, which is also probably the worst crawling section on Snowy on the current route, and were quickly back in the nice walking passage with plenty of shoe cover spots near Turtle Junction.

Overall, the trip out was fairly uneventful. There was one spot where a magic carpet slipped out from under me on a slope and I stepped onto the mud in my clean shoes. I did have to take 10 minutes after that to clean the mud out of my shoes, but that was no big deal. It happened on a magic carpet, so Snowy didn’t get dirty at all, and I kept the magic carpet clean. In fact, while I was cleaning my shoe, Ben staked down that tarp so it shouldn’t slip again. Many of the magic carpets need maintenance work like that—either staking down, or lengthening to get them away from obstacles, or cleaning. I’m definitely gonna submit some proposals to lead some route maintenance trips when they open up trip proposals for next year.

At 4pm we got to Turtle Junction and had to bid adieu to Snowy, for now at least. James, Beth, and Ben will surely be returning within the next year, and they might even do another trip this season before the BLM closes the cave for bat hibernation in November. I will be doing a few more trips this season, so my farewell to Snowy was only temporary.

Since I no longer had to care about keeping myself or any of the cave clean from this point, I didn’t even bother changing out of my clean Snowy clothes. In fact I took my shirt off to do the last part of the cave, which involves some strenuous crawling. I caved out in wellies, flowery short shorts, and no shirt, which might just be the strangest caving outfit I’ve known. But it was certainly a good/effective outfit given the circumstances. We were out of the cave at 5:15pm, 11 hours after we left Midnight Junction. A little under an hour faster than the way in. Not bad given that we were carrying extra weight and were tired from 4 days straight of caving and from waking up at 4:30am.

When we got to the surface, Ron Lipinski, Steve Peerman, and Kathy Peerman were waiting at the bunkhouse for us, and they had pizza! Thanks so much guys! We regaled them with tales of our epic trip and showed them photos while we ate and cleaned off our gear. They were psyched to hear that we surveyed 4000 ft, and left a great walking lead or leads both days! Our trip increased the cave’s surveyed length from 52.77 miles to 53.49 miles, we later found out.

When I dumped my pee out while emptying my pack and cleaning my gear, I realized that I only ended up peeing under four liters over four days. Much less than the five liters I peed in three days on my last Snowy River camp trip. I didn’t feel particularly dehydrated this trip. I attribute this low pee volume to three things I did differently than last time. First, I drank very little coffee. I slept well enough that I didn’t need it to feel awake and energized in the morning, and I pooped regularly in the morning without it. Second, I ate lots of salt. Apparently this can actually make you drink less water and pee less, which is unintuitive. Third, I followed a habit I’ve been building around water consumption in hot caves: when stopping to drink water, I force myself to wait a few minutes to cool down before drinking any water. I find that right when I stop for a break, I’m hot and will drink tons of water if it’s given to me. But if I wait even a minute or two, I cool off and don’t feel the need to drink that much water—a few sips will do it for me, rather than half a liter.

I felt pretty good about what I packed this trip. I’ll make just some minor changes next time. One thing I would not bring next time is a third liter of water. Two Nalgenes for drinking and one for peeing during the day (and a dromedary to carry it all out the last day) is plenty. I could have brought more food, although what I had was adequate. I never wore my fleece survey layer, although I like to always have a warm layer in case someone gets hurt and needs to stay put for a while. Maybe a thinner one would work next time. A long sleeve shirt and no elbow pads would save pack space over a short sleeve shirt and elbow pads, but it may not be worth the heat cost. I definitely want a plastic putty knife next time. Maybe I can pare down my personal first aid kit, since there are stashed first aid kits at various points in the cave up to Midnight Junction.

After cleaning up all my gear and leaving it to dry in the gear shed, I started the drive back to Albuquerque. I forget exactly what time I left, but I made it back at a reasonable hour, early enough that work the next day felt great. I look forward to returning to the cave and all of its excellent leads! Thanks to James, Beth, Ben, our surface watch Ron, the BLM, and the Fort Stanton Cave Study project for making this trip happen.

Now that I’ve been on two far Snowy camp trips, I am allowed to lead my own exploration trips. I’ll certainly be doing that next year, after the next cycle of trip proposals this winter. Stay tuned to see what I get up to!