Lechuguilla

3 days in a beautiful and hot cave

This post, like many of mine, is fairly long and rambly. It’s written partly to share a story with others, and partly to record information about the route/timing/water consumption/etc. to have as a reference for future trips. Consider scrolling to the pictures and reading near them to get to the good stuff if you don’t want to read all of my extended monologue.

This past Memorial Day weekend, I did a 3-day camp trip in Lechuguilla Cave. Lechuguilla Cave, or ‘Lech’ as cavers call it for short, is in Carlsbad Caverns National Park, but it is not connected to Carlsbad Caverns (the subject of my last post). Lech is longer, deeper, and in many ways, more spectacular than Carlsbad Caverns.

Lech has 152 miles of surveyed passage that forms a dense maze of huge boreholes, tiny crawls, pits that bore deep into the earth, and everything in between. There are still leads remaining in the cave, so that 152 mile number will surely continue to grow. At 1589 ft deep, it was the deepest cave in the US until Tears of the Turtle Cave in Montana overtook it in 2014.

The cave is not known for its length and depth so much as the incredibly decorated, beautiful nature of much of its passage. Lech is filled with massive, pristine, and awe-inspiring rock formations found only in caves, such as stalactites, stalagmites, and many even more bizarre features. For that reason, access to the cave is strictly controlled by the park, and people can only go for approved purposes such as exploration, scientific research, or other tasks that support these goals.

Both exploration and scientific research trips in the cave have slowed down in recent years due to various policy and personnel changes in the park. But this past Memorial Day, I got invited on a trip there. With 6 people/2 teams, there would be multiple objectives. The task for our 3-person team was to help replace aging ropes in a deep pit series in the cave. Because this pit, called the Kansas Twister, is in a somewhat remote section of the cave, about 6 hours of travel from the entrance, we would do it as a 3 day camp trip. 1 day to travel to camp, haul a bunch of rope into the cave, and do some minor objectives near camp; one day to haul the ropes out to the Kansas Twister and replace them; and one day to exit the cave and haul all the old rope out of the cave.

The other thing that makes this cave noteworthy besides its large, beautiful decorations and besides its long, mazy character is its hot temperature. It’s 68 degrees, which may not sound hot, but the 100% humidity makes it very difficult to cool down once you get warm, as sweating isn’t very effective at cooling you down in those conditions. So the cave is a very comfortable temperature when not moving, but the slightest bit of exertion gets you very hot. I run pretty hot when caving. In fact, I consider it my Achilles’ heel of caving; it’s the best way to defeat me on a long hard trip! So I made it a point to drink tons of water in the days leading up to the trip, to front load my hydration as much as possible. I was definitely a little bit nervous about the heat leading up to the trip.

After work on Friday the 23rd, I drove straight down to Carlsbad and stayed at my friend Georgia’s house. She would be on the trip too. The third person on our team, Michael, arrived at 2am after a marathon late-night drive, long after I had fallen asleep. I went to bed excited to spend 3 days camping in one of the world’s most spectacular caves, but also a little bit anxious to see what the heat would do to me.

Saturday, May 24th

We took our time leaving the house Saturday morning, and didn’t get to the trailhead until around 11. Hunter, Garret, and Karla, the other 3 on our trip, arrived much earlier, around 8am, and had the benefit of the cool morning air for the approach hike. By now it was quite hot out, in the 80s with full overhead sun, although a faint but steady breeze made it feel relatively pleasant. I chugged as much water as I could before starting the hike, as I didn’t want to lose my well-hydrated state that I had spent so much effort cultivating the previous few days. After packing the ropes that the other team left us to carry to and into the cave, it was 11:15 and we were off to the cave.

The hike starts out following the Guadalupe Ridge Trail from the Walnut Canyon Desert Drive route in the park. After about a mile on the ridge trail, you leave the trail and go up a ridge on your right (North). There is allegedly a trail here, although we never found it on the way in. After a while spent walking around in circles looking for the trail, I decided to skip that and just walk in a straight line in the direction of the cave and ditch the others (sorry). This is a classic move I pull: I’m not very good at finding nor following trails, but I don’t mind bushwhacking and am always down to trudge through the shortest-but-probably-not-most-efficient route to get from point A to point B.

I also took all the rope so that the whole group would get there faster. I got to the cave around 1pm. Despite hiking through the midday sun on a hot late May day in Carlsbad, I felt like I was at a pretty good temperature. I figured maybe this would bode well for the cave, which is notorious for being very hot, and would be the hottest cave I’ve ever been in. Although the dry desert heat, which I typically do very well in as I sweat a lot, is certainly a different beast than humid cave heat, which is less affected by sweating and which I typically do worse in. I was still anxiously waiting to see what the cave air would feel like.

I drank half a liter of water and left the other half of that bottle on the surface, stashed there for the exit 2 days later. I hung out for a bit in the shade provided by the entrance sinkhole and cooled off while waiting for the others. They arrived shortly after me, and we were all in the cave by 2pm.

After dropping the entrance pit to a ledge partway down, my first impression was that it was not obvious which way was the way on, and I wondered how confident the original diggers were that they were digging in the right spot. Lechuguilla was famously just a surface pit with a dig blowing air for several decades after it was discovered. Cavers dug at it for many years, following the air, but apparently never completely sure that they were digging in the right spot, as air was coming from several spots in the entrance pit. Clearly they were digging in a good spot, as this 150+ mile cave is certainly the greatest cave digging success story ever told.

After squirrelling down into a little hole in the large chamber in the middle of the entrance pit, past another 10’ drop, I arrived at the airlock. My second impression of the cave was that the airlock and subsequent shoring around the old dig was an extremely impressive engineering/construction project. I was expecting that and had heard much about it before, but seeing it in person still imparts more awe than anyone’s description can. The airlock is a series of two stainless-steel, standing-height doors on opposite sides of a room that 3+ people can stand in. On the side going into the cave, a 3 ft diameter stainless steel tube bores down into the Earth at a 70 degree angle for about 40 ft, with a ladder going down it. All of this was dug open, then reinforced with stainless steel tubing, by cavers over many years. I thought that some of my dig projects got a little ridiculous when they lasted a month or two; but this multi-year effort was clearly in its own class!

The tubing pops you out into a small walking passage. There I followed a trail flagged with orange flagging tape, which would be there pretty much the entire way to camp, and then some. At first I thought the flagged trail was a little excessive, but it later became apparent how useful it was when the mazy character of the cave asserted itself. The cave is full of rooms where multiple similar-looking tubes shoot off in many different directions, and there would be no obvious way to tell the way on if not for the flagging.

The small walking passage continues for a few minutes to the first of many rooms with pools and formations. I’m always amazed when I see water in caves in the Guadalupe Mountains, given how dry it is on the surface, but it often hides just beneath the surface, and Lech was no exception. The temperature here felt quite reasonable; not much hotter than other Guads caves I’ve been it.

2 short, low-angle ropes interrupt that small walking passage before you get to the first big pit in the cave, Boulder Falls. Boulder Falls is a 150 ft pit, freehanging most of the way that starts out large and bells out to become huge at the bottom. At the bottom of the pit, I stashed a half-liter of water for the way out and waited for Georgia and Michael while taking in the views of the massive chamber I was sitting in the center of. The others stashed some water there, and we continued walking/scrambling down the trail, as the huge chamber we just dropped into continued downwards as a similarly huge borehole.

Shortly below the bottom of Boulder Falls, I noticed a spot where the temperature suddenly changed. Above this one spot, I thought that the temperature wasn’t so bad, and this was gonna be easy. But for some reason, there was one spot where the air suddenly changed from cool, not-totally-humid aid that seemed fresh, like it was from the surface, to warm, humid, thick cave air. The heat hit me like a ton of bricks, and I could tell that I was gonna be in for a hot, sweaty 3 days. The dry desert in the 80s with full sun at high noon felt cooler than this.

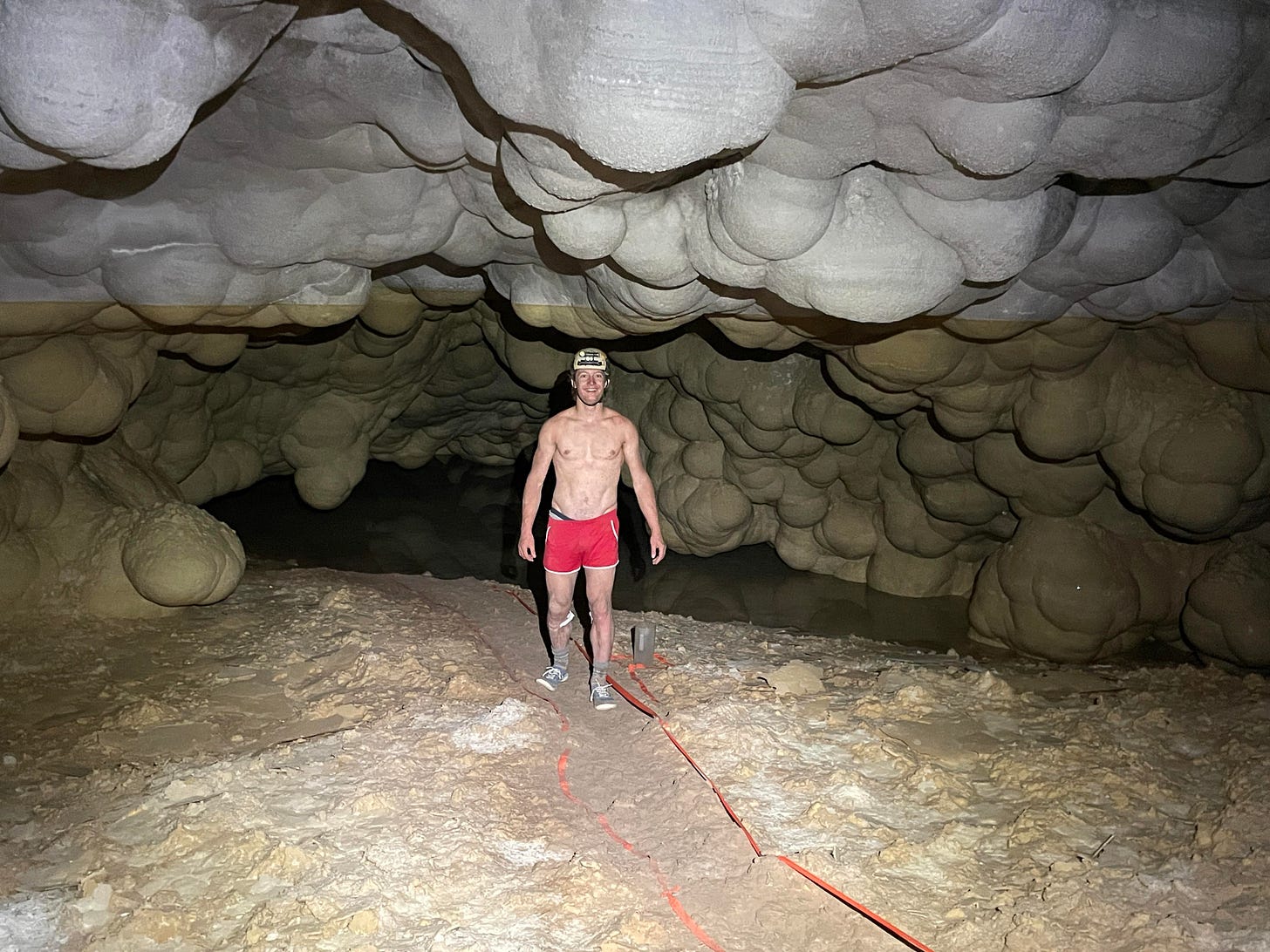

I was caving with no shirt and short shorts at this point, because the cave passage was so friendly and wouldn’t tear up my skin, like most caves would with that (lack of) outfit. So while I was sweating profusely, I felt comfortable enough.

The borehole below Boulder Falls eventually becomes full of white gypsum blocks, at which point it’s called Glacier Bay. There, probably because gypsum is more water soluble than limestone, the passage opened up into even bigger borehole, at least 100 ft tall. It also started branching off into several boreholes that all continued in different directions into the Earth, ominously fading into blackness. The branching boreholes were inviting (I couldn’t help but wonder where all those passages go!), but also ominous: they had a distinct mazy character to them, and the way they faded into blackness as far as your headlamp could illuminate them suggested that it would be very easy to get lost by wandering around in there. This is where the flagged trail running through the passage became essential.

The trail snakes between huge gypsum blocks, and scrambling around and between them makes Glacier Bay fairly high-effort for a large borehole. The gypsum forms distinct shapes and features rarely seen in limestone that were fun to admire on the way down, such as huge fluting, sharp fins, shiny polished rock, and circular holes going straight down from ceiling drops eroding channels into the rock.

Glacier Bay ends at another notable feature I had heard much about: The Rift. The Rift is a huge crack in the Earth that goes down at a 70 degree angle and continues left and right from the end of Glacier Bay. A short rope leads up to a ledge in the middle of The Rift that continues to the right, towards the rest of the cave. For much of The Rift, you can walk on ledges that continue as easy walking, although just as often the floor disappears and it is apparent that you are right in the middle of a several hundred foot crack. Much like the branching tunnels of Glacier Bay, when you can see down The Rift it fades away ominously yet invitingly into blackness as far as your light will illuminate. At these exposed sections, fixed traverse ropes make for casual travel, as long as the exposure doesn’t get to you. Getting across the first time to get the ropes set up would have been interesting, although probably not too challenging, as the diagonal nature of The Rift means you could probably slab traverse across without too much difficulty. The Rift was some of the more sporting section of the cave on this trip, as it had a few tight spots where I had to take my pack off and finagle it through. I had two coils of rope, 390 ft of 11mm pit rope in total, tied to the outside of my 42 L camp pack, which loved to get stuck in the few sections of the cave that got a little tight. With all the rope I was carrying, and the excessive amount of water I had, my pack probably weighed 40 pounds. Taking it off and shoving it through a few tight spots was fun, and reminded me that I was in a cave, not just a scenic hike. The exposure and spots where you wouldn’t want to fall also added to the fun, although the traverse ropes make it so that a fall would be merely undesirable, but not dangerous.

After The Rift, you get to the first junction in the cave, where the orange flagged trail splits and goes 2 ways. This was EF Junction. I left another half-liter of water for the way out and took stock of the cave so far. With the most strenuous part of the journey to camp done without me overheating, I was feeling pretty good about the temperature of the cave. We took a quick jaunt down the right branch from EF Junction to look at a pretty flowstone room, then continued down the left branch, which was the way on to camp.

A few more minutes of walking and one more traverse ropes led to the next junction in the cave. A pit rope went down a pit on our right, while walking passage continued straight ahead. The pit had flagging with a label indicating that the Western Borehole was down that way. The pit is The Great White Way, and it was our way on. Georgia went first, I followed, and Michael brought up the rear. The Great White Way is a series of low-angle, somewhat tight ropes that were kind of annoying. But they went quickly, and after several ropes we found ourselves once again in a huge borehole. We stopped at the bottom of the pit for food and water, as this would be the last good spot to stop before camp. While it’s possible to stop in the borehole between us and camp, it’s full of large, uneven breakdown, without many good flat spaces where three people can hang out, so Georgia (the only one who had been here before) said we should fuel up and hydrate here and power through the rest of the way to camp. I finished my second liter of water, finished the second sandwich I packed in, and continued onwards to camp.

This next section of cave had several sequential names that I forget, because it all seemed like one continuous passage. It was a large borehole, although the trail takes you around, in between, and sometimes even underneath large boulders that make travel very scrambly and somewhat high effort. Going between and underneath the boulders often makes it seem like you’re in small passage, even when that space between boulders is in the middle of a huge chamber.

In this section is the first gloves-off part of the cave, called Deep Secrets. A small plastic sign marks the start and end of the gloves off section, where you have to stem and use your hands to push off pristine, clean flowstone. Even with gloves off, it’s difficult to keep everything clean. You have to take your pack off and move it with your bare hands, and the pack and rope are somewhat dirty and rub against the walls. At least the bag is likely cleaner than gloves. Touching smooth, clean, wet flowstone felt a bit like eating forbidden fruit, as that is typically a no-no when caving. However, in this spot there is no other way to get through the passage, so you just take your dirty gloves off and get it done. Touching it with bare hands too made it feel exciting; I felt very connected to the cave.

We got to camp, which is in the middle of this borehole where it finally gets to a section with flat dirt floors, at 7pm. Hunter, Garret, and Karla were all lying down at the highest camp spot up on a terrace, patiently waiting for us. We rushed to greet them all and rave about what a fun trip in it was. I had met Garrett and Karla briefly at Fort Stanton, but didn’t know them well, so I reintroduced myself. I knew Hunter quite well, but I hadn’t actually caved with him before. I was excited to finally cave with him, on his first camp trip to boot.

At roughly five hours from the entrance to Deep Seas Camp, we were a little on the slow side, but within the normal range of travel times. The slow travel time definitely helped with not overheating. I made it to camp while only drinking two liters of the 5.5 liters of water I planned on bringing! Hunter, who like myself tends to overheat badly in caves, was jealous, as he had to drink 5.5 liters of water on the way in.

We unpacked a bit and started to set up camp, although not all the way, as we wanted to continue caving that night. Garret and Karla took a somewhat secluded couple’s spot. Georgia took her own private spot. The rest of The Boys (Michael, Hunter, and myself) took the biggest spot high up on that terrace and declared that terrace the Dude Bro camp spot. We all bro’d out up there on that spot the whole trip. As did the other 3; our spot was the central hang out spot when we were at camp and could easily fit all 6 of us.

I unpacked my bag and made everyone chuckle when I unearthed a full 3.5 L plastic jug of water that I didn’t touch on the way in. At least I was fully prepared with plenty of water! I surprised even myself when I unearthed yet another full 1 liter Nalgene that I had forgotten about! I was supposed to stash that somewhere for the way out, but I forgot about it and carried it all the way to camp. So I ended up carrying 6.5 liters of water to camp, and only drank two of them. That’s 13 pounds! Oh well. Since I only drank 2 liters of water on the way in, and had one liter stashed on the way out and a half liter at the entrance, I wouldn’t have to carry much water for the way out at least.

After unpacking and partially setting up camp, it was time to continue caving. The night was young! One objective close to camp that Hunter, a cave manager at the park, wanted to do was to inventory some sites in the cave where there was science equipment stashed from long ago in unknown condition. This was in the Pellucidar area of the cave, about 10 minutes from camp.

Michael was pretty worked from the trip in, so he decided to stay back while we went to Pellucidar. He wanted to make sure he had energy for our big day tomorrow, replacing all the ropes in the Kansas Twister. So the five of us followed Garrett, who knew the way to Pellucidar, out of camp back the way we came.

After five minutes on the trail, we exited off the flagged trail to the right and got on an unmarked but still obvious and impacted trail of brown dirt going through white gypsum. As the flagged trail descended down a slope in the main borehole, this side trail stayed high and angled towards the passage walls, where an attractive-looking tube shot up into the ceiling. The tube was not too steep, 60-70 degrees, and stepped out, so Garrett easily scrambled up it, and we all followed to a ledge. The scramble was was easy, but it was on loose popcorn-and-dirt ledges that all seemed like they were about to break off.

From that ledge, a rope led up a move vertical part of the tube. While Garrett climbed the rope, I looked at the tube, which was likely free-climbed first to get the rope up there. Lechuguilla Cave is in a federally designated wilderness area, which means no power drilling. Hand drilling a bolt is arduous and time-consuming (takes about a half-hour), which means that climbs to access new passage often require a combination of bold free-climbing, sketchy aid climbing with creative trad gear and pitons, and laborious hand-drilling. Much of Lechuguilla was explored this way, including the Kansas Twister that I was to see tomorrow. I tend to think of myself as a fairly bold climber, but I’ve done very little of that kind of bold climbing for cave exploration purposes—all my exploration climbing in caves has been with a power drill. I know there are more leads like this in Lechuguilla, and I would like to explore them! So I am always thinking to myself when I encounter a passage that was explored via climbing, “could I have climbed this”? For this tube leading up to Pellucidar, I thought the answer was yes, but it would be a bold climb for sure.

Atop that rope was yet another large Lechuguilla borehole, this time filled with much more decorations than the previous ones. Aragonite bushes and stalagmites lined the trail that weaved through the borehole. While Hunter checked out some science station, I simply wandered around the trail and admired the formations, which I rarely have time to do on cave trips.

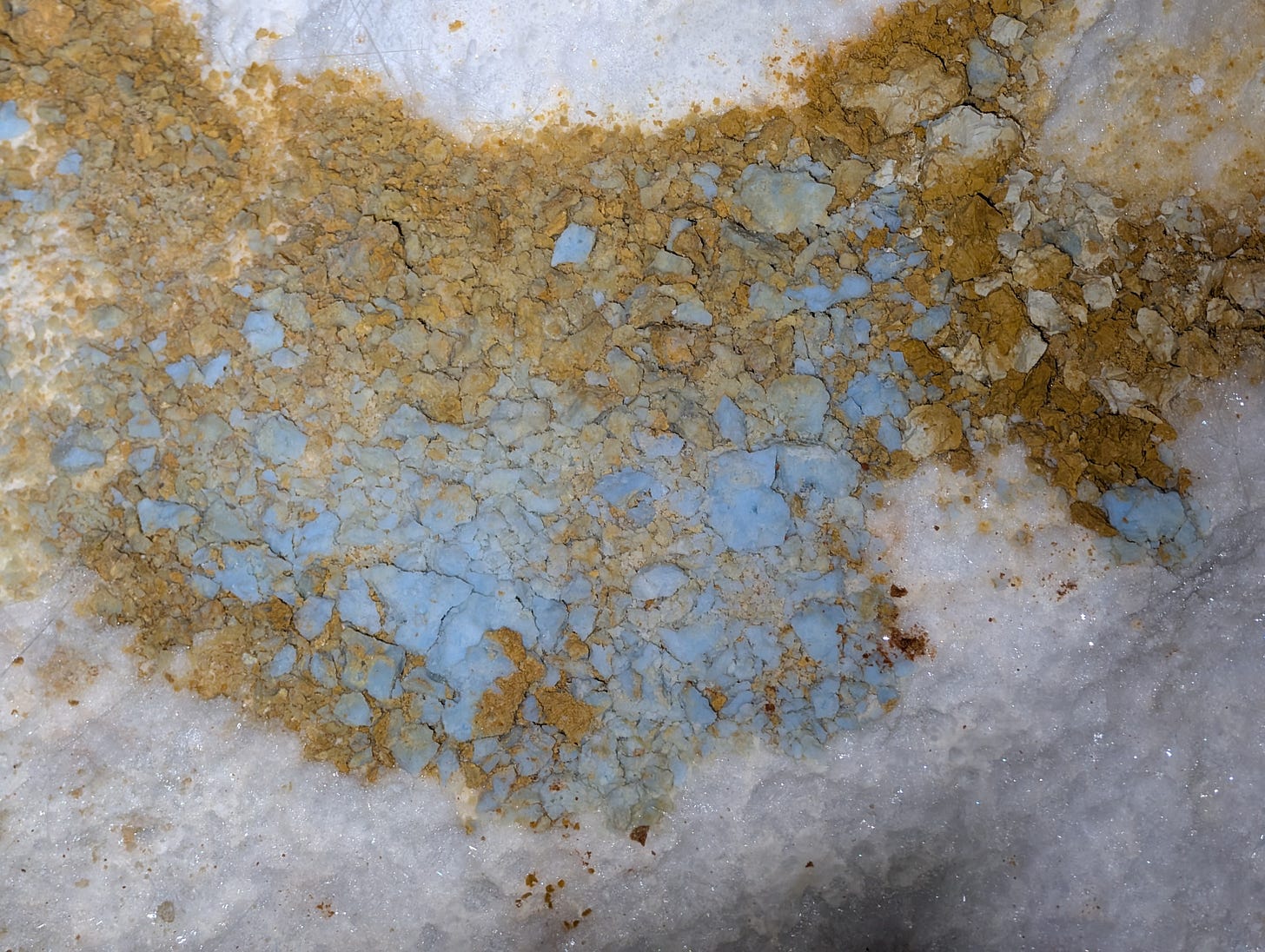

Garrett called our attention to a unique formation at one end of the hall that was apparently known about in only a few places in the world, this being one of the best examples. Subaqueous helictites. They were in a pool that was just beyond a small space that only one person could look through at a time. After Garrett found it, he called Hunter and everyone else over and had us look at them one at a time. I didn’t expect much, as I have seen a ton of helictites, but these were astounding and I audibly gasped when I saw them. They were tendrils of spaghetti-like rock growing at all sorts of funny angles, from the surface of a pool downwards, as the water in the deep pool turned rich, vibrant turquoise.

Those subaqueous helictites looked only superficially similar to the helictites I’ve seen in other caves. Although they both resemble spaghetti-like strands of rock growing in all sorts of funny directions, standard helictites are more curvy and bulbous, while these have a distinct angular look and feel to them.

Although the subaqueous helictites looked very different than standard cave helictites, they did remind me of one cave formation I had seen before. The Flying Spaghetti Monster in Helms Deep, a cave in Tennessee. The Flying Spaghetti Monster kind of looks like helictites, but is definitely distinct. It consists of straighter segments of rock that shoot out at several different angles and mostly stay at the same direction with a few sharp angular bends.

Helms Deep is clearly phreatic and likely formed while submerged. So it’s possible that the Flying Spaghetti Monster and similar nearby formations could have formed while submerged via the same process that forms the subaqueous helictites in Pellucidar in Lechuguilla.

Garrett spent some time looking for another room called the Diamond Room while I sat around admiring the pretties. He couldn’t find it, so it was time to go back to camp. Hunter didn’t want to do the loose free climb down from the ledge below the rope that goes up into Pellucidar (the one with the popcorn-and-dirt ledges that all seem like they’re about to crumble), so I volunteered to go back to camp, grab one of the ropes there, and bring it back up. I downclimbed the steep tube, which was much less pleasant on the way down than up, then power walked to camp to retrieve a rope. I grabbed a short 100 ft rope and brought it back up the tube to the ledge. I rigged it to a boulder, and those still left on the ledge used it to descend safely. I was the last one down, and did the downclimb one last time without a rope after throwing it down so we could use it elsewhere in the cave. I don’t blame him—that climb is a little sketchy, and if people return to Pellucidar with any regularity, we should leave that climb rigged.

There were no more short, nearby tasks to do, so it was time to head back to camp. I finished setting up my camp spot, made my dinner (my classic Dinner Mix, this time with extra bacon), and did a run to the water supply to have plenty of water for the night and morning.

Georgia took me to the water source, a beautiful pool called Lake Louise, five minutes away from camp. At this point I was just caving in my camp shorts (very short) and my barefoot-style shoes; no kneepads nor harness nor shirt. I was caving as close to naked as was reasonable! It actually felt pretty nice. Normally when caving I’m armored up, with long pants, stiff shoes, kneepads, and other protection. Caving with minimal stuff on me in a cave friendly enough where that was feasible felt refreshing and (I’m being a bit melodramatic here) liberating. Especially with my barefoot-style shoes, I could feel all the details of the 3d structure and texture of the ground through my feet. Whenever my bare skin touched rock, I felt a pleasant frisson of cold on my skin, much stronger than it would be if mediated by a layer of clothing. I felt very in touch with the medium.

Despite all the pretties I had seen that day, I was not prepared for Lake Louise. I was astonished yet again by the cave’s beauty when I got there! It was incredibly decorated in a totally different way than Pellucidar. Instead of aragonite bushes and stalagmites, it was colorful mammilary formations. Cave mammilaries are smooth, spherical blobs of rock. The ones here were huge, watermelon-sized, and they abruptly switched from pearly white to a vivid yellow color at what must have been an old waterline. The current waterline of Lake Louise is 10 ft or so below that old waterline. The mammilaries at Lake Louise are so classic, in fact, that the NSS website’s page on mammilary formations has photos of cavers collecting water from Lake Louise.

Georgia showed me the water collection protocol (there is a whole sequence of steps you take to avoid potential contamination of the pool), and we filled up several bottles that would last us all through the morning. When we got back to camp, there was one last surprise waiting for us. Garrett and Karla packed Nacho Libre masks in a bunch of different colors into the cave for us to wear as a little joke. They looked cool, and we played some music, danced, and ran around wearing our masks for a bit, until the foam on our faces made us much too hot. I like when people bring little Easter eggs on cave trips like that—see my Silent River Cave post for an example when Sam Marks brought some colorful patterned ties as novelty items to wear while partying it up on a cave trip. Maybe I should bring the novelty items on my next long cave trip. I’ll take suggestions in the comments…

We kept the music going a little while longer and kept dancing long after the heat forced us to shed the masks. Around 11 pm, we started to approach the going-to-bed state, and we decided on an 8 am wake-up time the next day. As various little tasks kept us up and midnight approached, I suggested a 9 am wake-up time. I wanted to give us 9 hours of sleep time, which I like to have if I want to perform at a high level the next day. Georgia loudly and enthusiastically agreed as soon as I finished my sentence; I figured out this trip that she is not exactly a morning person. Hunter changed his alarm from 8 to 9 and we were off to bed.

Sunday, May 25th

I woke up to Hunter’s alarm on a mostly-flat sleeping pad. Oops; I should have checked to make sure my pad was in good shape before packing it on the trip. Oh well, at least I slept well on it. The cave is warm enough that a sleeping pad isn’t super necessary as insulation from the ground; it just adds comfort when sleeping.

I ate my breakfast of oatmeal with peanut butter and dates, which was different from my usual choice of more Dinner Mix. It was way too much food and I had to try kind of hard to finish it. Despite drinking only 2 liters of water when getting to camp the previous day, I packed 5.5 liters of water for the day. My 3.5 liter plastic jug, and 2 Nalgenes. It was very possible that today could have 15 hours of caving instead of 5. My snacks for the day included a smaller amount of cheese and fatty cured meats (a staple caving food), and more sugary snacks like dried mangoes and peanut M&M’s. I was trying a more sugar-heavy snack strategy in the cave for heat management purposes. Fatty foods tend to fuel me for longer, but they make me hot, as fat takes energy to digest. So I figured more frequent smaller sugary snacks, and being slightly calorie-deficient, would help me stay a bit cooler.

After packing my snacks, my camp bag felt very empty still. I would just have to take more rope! I took 2 cave coils of rope, and off we went, around noon. I started out wearing the cave coils around my shoulder, but I quickly got annoyed with how they dug into my shoulder and interfered with my walking and vision, so I tied them to my cave bag instead.

We left camp around 11am, as one group of six, because we were all going the same way for most of our commute. All of our intended destinations were at least an hour down the Western Borehole, so we all headed that way together. From camp, we started by going towards Lake Louise, then turning right instead of taking the left that leads to the water source. Just after the right turn is a series of two short up ropes (‘the ABC ropes’). I remember thinking that these ropes definitely seem like something I could free climb to explore/get the rope up the first time, before touching a fin of rock and hearing a big reverb sound, like the rock was about to fall off. Loose rock will get you!

After those ropes we popped through a hole that brought us into a huge spherical room coated in pristine white gypsum. There was a perfect large flat boulder that I could lie down on and admire the room from while waiting for the others. If I even slightly changed the angle of my head while looking around the room, the walls would sparkle brilliantly. I felt like I was sitting down in the middle of an IMAX theater, lying down on my comfy flat-topped boulder and enjoying the sparkly light show as I looked around.

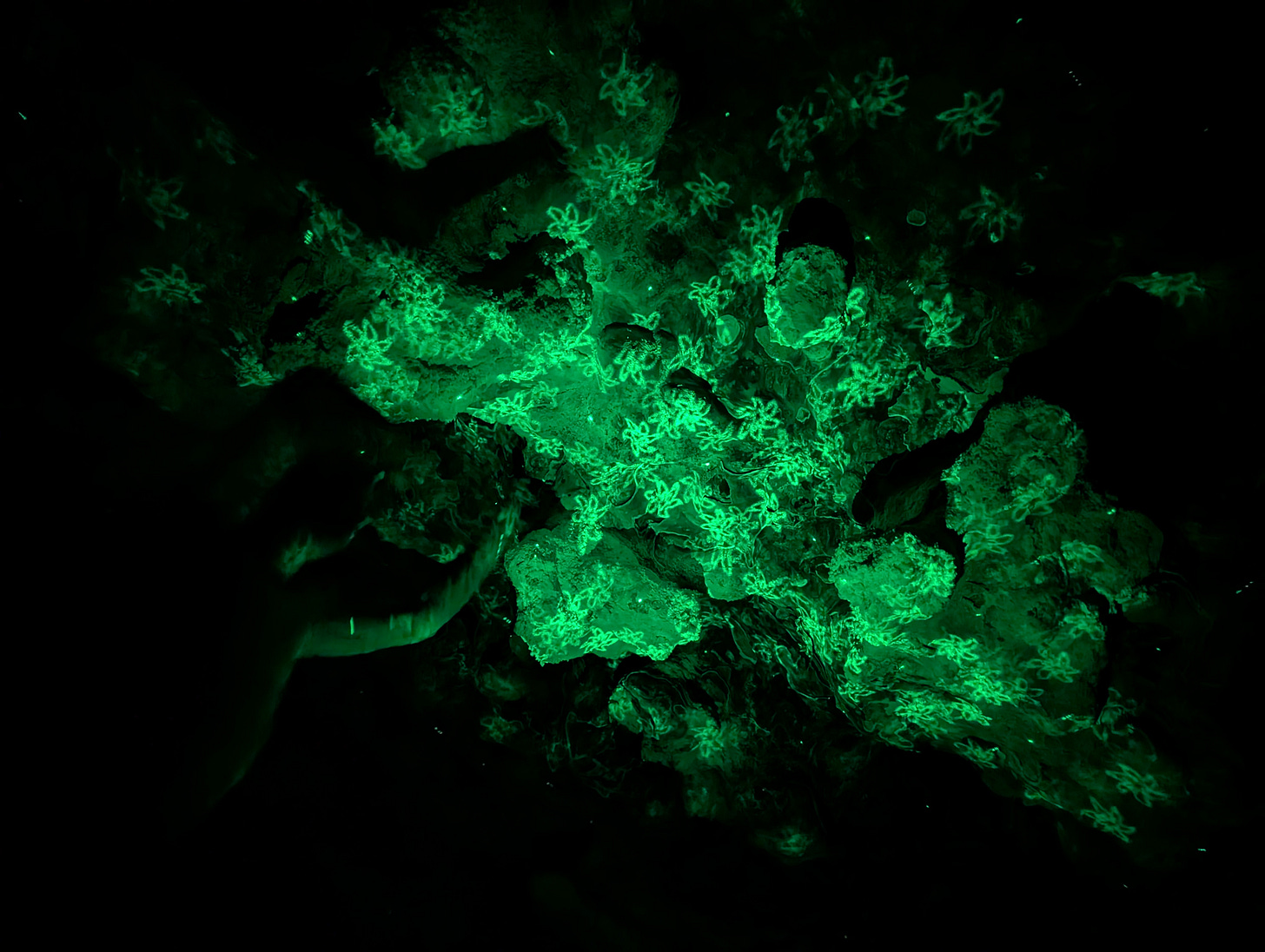

When the others finished the ABC ropes and we kept walking, this sparkly chamber got even better. As we followed the trail down the chamber, it grew even bigger, from 50 ft across to probably 100. As we crested a hill in the trail, I got a good long view down the chamber and saw it continue indefinitely as far as my headlamp could illuminate it, and beyond that as it faded into blackness. This was not just one room, but a whole passage with this huge circular cross section and sparkly gypsum lining all the walls and floor. Garrett announced that this was the Western Borehole, and I now knew why I had heard about this passage from several different sources before. It was one of the most incredible cave passages I had ever seen.

As we continued down the Western Borehole, it stayed blissfully pleasant and friendly. It had mercifully small breakdown in its floor, which made travel through it feel like actual walking, not climbing/scrambling as was the case with the previous large boreholes that were full of huge breakdown (Glacier Bay, and all the passage between the Great White Way and Deep Seas Camp). It was consistently coated with sparkly gypsum the whole way, with beautiful formations such as aragonite bushes, huge drip holes, even an aragonite bush growing out of a drip hole like it’s a potted plant, and chandeliers growing out of the ceiling. We took one break for food/water/enjoying the scenic view at a notable formation called the Three Amigos. We figured that a formation with that name was a perfect time to don our Nacho Libre masks and take a silly group picture.

There were two spots in the Western Borehole that I thought had strange and suboptimal rigging. One is a mandatory traverse line on a very exposed walk down a narrow sloping ledge lining a pit that only has one-bolt anchors on each end. Not cool! Another was a rope that ended right in the middle of the exposed section, without protecting the parts of the ledge walk with the highest fall exposure and likelihood. Whenever I lead a trip back there, I’ll be beefing up that rigging with something better.

After two splendid hours of scenic walking down the Western Borehole, it was time for our teams to split up. We were at the Leaning Tower, where the trail branches off to the right towards Emerald City and the Kansas Twister (and many others), and left towards the Far West and Oasis (and many others). The Leaning Tower at that intersection is another awesome and unique formation. It’s a thick (3 ft) pair of stalagmite and stalactite that don’t quite meet to form a column and are covered in bulbous popcorn.

From here, the teams were nominally Garrett, Karla, and Hunter; and Georgia, Michael, and I; but Garrett came with us at first to show us the way to the Kansas Twister and climb up it with us, as the route to there was not clearly flagged the whole way like the main travel route down the Western Borehole was. Karla and Hunter did some smaller objectives close to the junction while Garrett was with us.

It was about 2pm then. We told the other team to expect us back at camp around 2am, but not to worry until 6am. I was excited that I was finally going to have a long, morning-to-morning day of caving! Even if it wasn’t gonna be a super difficult day, it would be a long day, which I like. My caving in New Mexico lately has been lots of short trips, which are still fun, but definitely leave something to be desired in me.

The right turn from the Leaning Tower took us down some small but still stand-up walking passage, then another right turn had us in some real cave passage, with some crawling and shoving the bag required. Nothing too hard, but at 68 degrees with a heavy bag full of rope to shove around, I definitely worked up a real sweat in there. It was intensely mazy, and the route was flagged with little breadcrumbs of flagging instead of the super obvious double-lined trail of the main routes, although it was easy enough to follow.

After a short length of crawling and otherwise more physical caving, we were back in small walking passage. It was full of vibrant blue-green colors, which I don’t see too often in caves. And gypsum hair, that sparkled more intensely than anything in the Western Borehole. Gypsum hair is always hard to get pictures of, as the real wow factor comes when you move around and it lights up with sparkles, but Michael did a decent job of capturing what it’s like.

Eventually, Emerald City opened up from small walking passage into a huge chamber, and we were at the Kansas Twister. At the top of a gravel slope lay the first of several ropes that would take us over 500 ft up, closer to the surface yet also more distant from the outside world. The previous weekend, at Virgin Cave also in the Guadalupe Mountains, James Hunter told me about how he got the rope up that first pitch, many years ago. He free climbed it, without a bolt kit or any other anchoring material, assuming he would find something to tie the rope to or just come back down. After realizing partway up that the latter was definitely not an option, he was relieved to find a small rock wedged in a crack above the difficulties that he could tie off to. I kept that description in mind as I climbed the rope.

And when I climbed that rope, oh boy, all I could think was, “James Hunter is a hardcore motherfucker”. It was a low-angle slope, but it was covered in loose dirt and didn’t have much in the way of good foot ledges, just slopey, dirty, sandy features barely protruding out of the slab. That would be a hairy climb for sure. James said he was young (25), dumb, and full of irrational exuberance when he free climbed it. I definitely had an immortality complex going earlier in my 20s and did some dumb shit, but I don’t know if I was ever bold enough to free climb something like that. Good work James.

Above that rope is a lower-angle gravel slope, and a good alcove in the wall where you can hide out of the rockfall zone below the next rope. We all went to the alcove, snacked and drank some water, and redistributed rope, because we left a 100 ft rope at the top of the slope we just climbed. I also stashed a liter of water there, as I had drunk barely any of the 5.5 liters I had hauled out there.

The next rope goes up about 100 ft to a huge arch bridging the gap between opposing walls of the pit. The wall is sheer vertical and would be unclimbable without a protracted 100 ft hand-drilling effort. And even then, possibly still unclimbable because the rock is total choss. So they got up there by—wait for it—using a slingshot to get a rope over the arch 100 ft up. My understanding is that nailing that slingshot took many attempts over several trips over the years, and that the operation that finally worked involved slingshotting very lightweight, narrow cord over the arch; using that to pull some paracord over the arch; then using that to get some real cave rope over the arch, that someone then climbed.

We all knocked rocks down on that pitch and the next few, so we went one at a time while the others waited above or below in that alcove. When I went, I was not super happy with the exposed walk across a steep gravel-and-dirt ledge that is necessary to get to the bottom of the rope. For most of the walk out to the rope, there’s a trail kicked into the gravel, as you can see below. But right before the rope, the trail disappears, and you have to slab across some bare rock covered with a fine layer of dirt, all above an exposed, steeper slope. You’ll totally die if you fall. I didn’t like that, although everyone else on the trip seemed totally fine with it. Maybe I went too low or too high, or I’m just getting soft.

At the arch is a rebelay, then another long freehanging pitch, then another rebelay right below a big ledge where everyone was hanging out, off rope, waiting. I got up there and enjoyed the view while waiting for Michael to join us. While he was on rope below us, I walked down the stoopwalking passage that departed from the ledge. It was actually really nice! Pristine sparkly white gypsum lined the walls, floor, and ceiling of the circular cross section tube. I stopped when the trail through the passage became not very impacted, just a few faint brown footsteps in fragile, mostly-white gypsum crust. I didn’t feel the need to go any further and impact a mostly-pristine area for some sightseeing that was not our main mission.

It was wild to see the arch in person, even up close and personal as I passed the rebelay on it. I had heard so much about that aid climb. When I was very new to caving, and didn’t even know what Lechuguilla was or that there were caves in New Mexico, I remember my good friend Christian who got me into caving telling me stories, that I kind of thought were fake, about people aid climbing up 500 ft domes via slingshot in long and deep caves out west. Now I was finally there, and it was definitely not fake.

I had also heard stories about how bad the rock was in the dome. That’s totally true! I knocked down several rocks at the arch, as did the others. And that’s after a good amount of people have traveled that route and cleaned things up. When Derek Bristol first went up to the top of the arch, so I’m told, the rock was so chossy that he declared the rest of the dome unclimbable and was ready to give up. But James Hunter, glory be to him, got it done and quested up the sea of choss, hand-drilling only a small handful of bolts in what has got to be one of the boldest yet also most successful aid climbs in American caving history.

From the ledge with the stoopwalking gypsum passage, another short low-angle rope led up to a ledge, then a longer freehanging rope led up to a bigger ledge. We did those pair of ropes one at a time. Then we went up the last rope, which has one rebelay (one at a time on that two-pitch rope, also go right at the rebelay as there are two ropes). After that, we were off rope and officially above the Kansas Twister, one of the most epic pits/domes in the US. I felt somewhat accomplished for getting up 500+ ft of rope without dying of heat stroke, although our real work in the pit had yet to begin: we still had to replace all the ropes in the pit, which we had yet to start, as we would do that on the way down. But first, it was time to see Oz! There are several miles of amazing passage above the Kansas Twister, and we wanted to see it.

Garrett showed us the way up some small tubes above the Kansas Twister, which on their own seemed not very impressive, seemed like they were about to end. I can’t imagine what James and Derek felt after getting up there, only to at first find some small stoopwalking and crawling tubes that constantly seemed like they were going to end. One of them was a crawl with bedrock on your right and a huge pile of rocks on your left that reminded me of the dig into Don Sawyer Memorial Hall in Fort Stanton Cave. With just a little more breakdown, this passage would have ended, and all that effort climbing the dome would have been for not much. But this breakdown-filled tube, thankfully, was just barely open, and just beyond it lie something incredible.

At the end of the small breakdown-filled crawl, you pop into a huge breakdown room at the bottom of a slope leading up into more passage. The abruptness of the change was especially cool: you immediately change from hands-and-knees crawling to a room so big you can’t see all the walls as you pop through a hole in a wall of the latter.

We followed a trail up the slope and realized that this huge room was just a depression in the floor of an even bigger borehole. This borehole was probably 200–300 ft in diameter, which I’m pretty sure is the largest passage I’ve ever been in. I think it’s bigger than the Triple Perspective Vortex in the Peña Negra section of Cheve. A handline at the top of that slope deposited us right in the center of the borehole, and all I could do was look around and be in awe of how far the walls and ceiling were from us, and how far down the tunnel we could see. You could quite literally fly an airplane in there. This passage is called Munchkinland, fitting with the Wizard of Oz theme, and because it makes you feel like a Munchkin in there.

Garrett told us at the top of the handline that Oz was to the left, and The Wizard, a great looking aid lead I wanted to look at and scope out for climbing, was to our right. Then he left; it was time for him to rejoin Hunter and Karla. Georgia, Michael and I were off to our own devices to wander around Oz, but not for too long as we still had our main task ahead of us: replacing 730 ft of rope on the Kansas Twister.

We all went left towards Oz, stopping at one spot to try to get some pictures that capture the scale (see above). Munchkinland ends and Oz begins when the ceiling drops hundreds of feet nearly to the floor, you have to duck under it for a few steps, and you pop back up into merely good-sized walking passage, about 10 ft high and 30 ft wide. After the ceiling duck is a T intersection; Oz goes both ways. Both ways looked decorated with more beautiful, sparkly gypsum and other formations. A trail of dirt weaved its way through the sparkly white floor.

I went right first. After a few minutes, this passage ended in a pit/dome with ropes going up and down. I started by going down, passed a knot in the rope at a bad rub spot, and got to a spot where the rope ran down smooth, clean flowstone. I didn’t want to dirty it up without knowing what the protocol was for that level of clean formations while on rope, so I went back up. I could have put on shoe covers and gone gloveless, but the rope was muddy, and it would be difficult to impossible to keep things clean while on rope. I didn’t want to create much impact for a side trip that was not our main objective in the cave, especially without knowing the standard accepted practice in that spot, so I went back up.

The rope going up from there went diagonally up and left in a J-hang like feature, although you could kind of walk across a small ledge in the lower part of the J-hang. I started up that, but ran into more clean flowstone that I didn’t want to dirty up, so I went back. Reversing the J-hang while in the middle of it was tricky, not something I had done before. I ended up changing over onto a Munter hitch (I couldn’t use my descender because it was in use to descend the other side of the J hang) then moving my ascenders to the other direction on the rope.

We went back to the T intersection and went left. Michael met us there after attempting some photogrammetry in Munchkinland. I don’t think it worked; the passage was too big. This passage off to the left was a similar-size, moderately-sized borehole, but brilliantly decorated, with aragonite bushes, pools, rimstone dams, velvet flowstone, and dense hanging gardens of stalactites lining the passage. We went extra slow down this passage, taking our time to admire the colors and take pictures.

The others stopped at a webbing handline. I went just a bit further, but knew at that time that it was getting close to the point where we had to turn around and start our main task for the day, replacing ropes. Just past that handline was an impressive display of velvet flowstone covering a wall. Just past the velvet, the trail weaved through a forest of huge aragonite bushes. Instead of a double-flagged trail to walk through, the trail was a series of individual footsteps circled with flagging tape, all precariously between delicate aragonite bushes on a steep slope. Walking through there would be like playing Operation with your feet. I figured that would be a good spot to turn around; there was a very real chance I’d break something trying to walk through there, and such impact wouldn’t be worth it for a non-exploration trip.

So, back to Munchkinland and back to the Kansas Twister we went. Before departing Munchkinland, I made sure to check out The Wizard, an excellent-looking aid lead at the end of Munchkinland on the other side from Oz. I saw a photo of this lead in the Lechuguilla book before the trip and when I heard it was on the way to where we were going, I had to check it out. It does indeed look excellent—a ~40 ft diameter hole in the ceiling with huge globs of flowstone oozing out of it. But it would be a tremendous effort to get up there: ~100 ft of hand-drilling up an overhanging wall. That will not be my first priority when exploration begins again in the cave.

At the top of the Kansas Twister, Michael descended first ahead of us. Georgia and I rerigged as a team. I rigged all the new ropes going down, and Georgia carried the old ropes down. It all went smoothly, if a bit slower than I expected. But rigging always takes longer than you think it will. One bolt was a perma-spinner and wouldn’t tighten down (the bolt shaft spun when I tried to tighten it). It’s the right-hand bolt on the two-bolt anchor on the last ledge before the two pitches that take you to the top of the Twister. It should be replaced on the next trip out there—hopefully by me!

I decided that the walk on the sketchy gravel slope out to the rope below the arch needs a traverse line, and I left enough old rope there, tied to the new rope at the bottom of the pitch below the arch, for a traverse line. I especially appreciated having that extra rope to grab onto while swinging over to the alcove where we wait out of the rockfall zone, as I had tons of old rope clipped to me and dangling from me, and it would be easy for me to misstep and fall there. I would like to do those rigging improvements on the next trip, in addition to fixing up the two ropes in the Western Borehole I didn’t love.

The rope on the arch, which goes from the ground below the arch to the ledge above the arch with the stoopwalking gypsum passage, could be a few feet longer. It reaches the ground, but just barely. You could get a few feet back by using a more compact knot at the top of that rope—I’ll also make sure to do that next time. Right now it’s a bunny ears knot on 2 bolts with super long ears, and a simple bowline and butterfly would use much less rope.

The one rope we couldn’t replace was the one on the low-angle slope, one pitch below the arch pitch. The one James free climbed. The rock that rope was tied to was wedged in a crack and buried under tons of small rocks and gravel, maybe by accident as cavers walked up the gravel slope above it, or maybe on purpose to make it more secure. I started digging it out while waiting for the others to rappel down, but it would have taken me at least an hour of digging, so I figured it was not worth the effort, and that next time someone would just place some bolts to make an easier-to-access anchor. I made sure to rebury the rock after deciding I wouldn’t be able to uncover the whole thing—Chesterton’s Fence, you know?

I rigged every rebelay with butterflies for maximum adjustability, and even rigged the rebelay on the arch with my signature three-butterfly style1. One butterfly for each bolt, and a third to have as an equalized clip-in point, because the bolts were spaced far apart. That kind of rigging—everything butterflies, and a third at Y hangs if it’s useful as an equalized clipping point—is my signature rigging style. Michael was a huge fan, although Georgia was not convinced of its utility over standard knots like bunny ears and fusion knots. I still have some work to do to convert my fellow cavers to The Butterflies Cult.

I stuffed as much old rope into my bag as I could and tied the rest of it to the outside of my bag. That was much better than on the way in, when I had a nearly empty, super floppy camp pack with two cave coils tied to the outside. Putting half the rope inside the bag made the bag full and stiff, which made it easier to tie one coil to the outside. And one coil snagged much less often than two coils.

We got to the bottom of the Kansas Twister at 11:24pm, and we were back at the Leaning Tower at our turn-off from the Western Borehole at midnight. Emerald City and the small passage below it were just as hot and sweaty as before. Climbing 500+ vertical ft of rope got me much less hot than that passage. I climbed fairly fast; maybe that breeze cooled me off!

The other team left a note at the Leaning Tower that they had departed for camp not long before us (their time on their note was something like 11:30pm). The hike back through the Western Borehole was long and scenic. We must have been at least a mile down the borehole, maybe two? We were back at Deep Seas around 2am. It was a 14-hour day out from camp. I drank about 3.75 liters of water out of the 5.5 I packed, and I ate most of my food but still had some from the day left over, and my one-liter pee bottle was well within capacity2. Perfect planning.

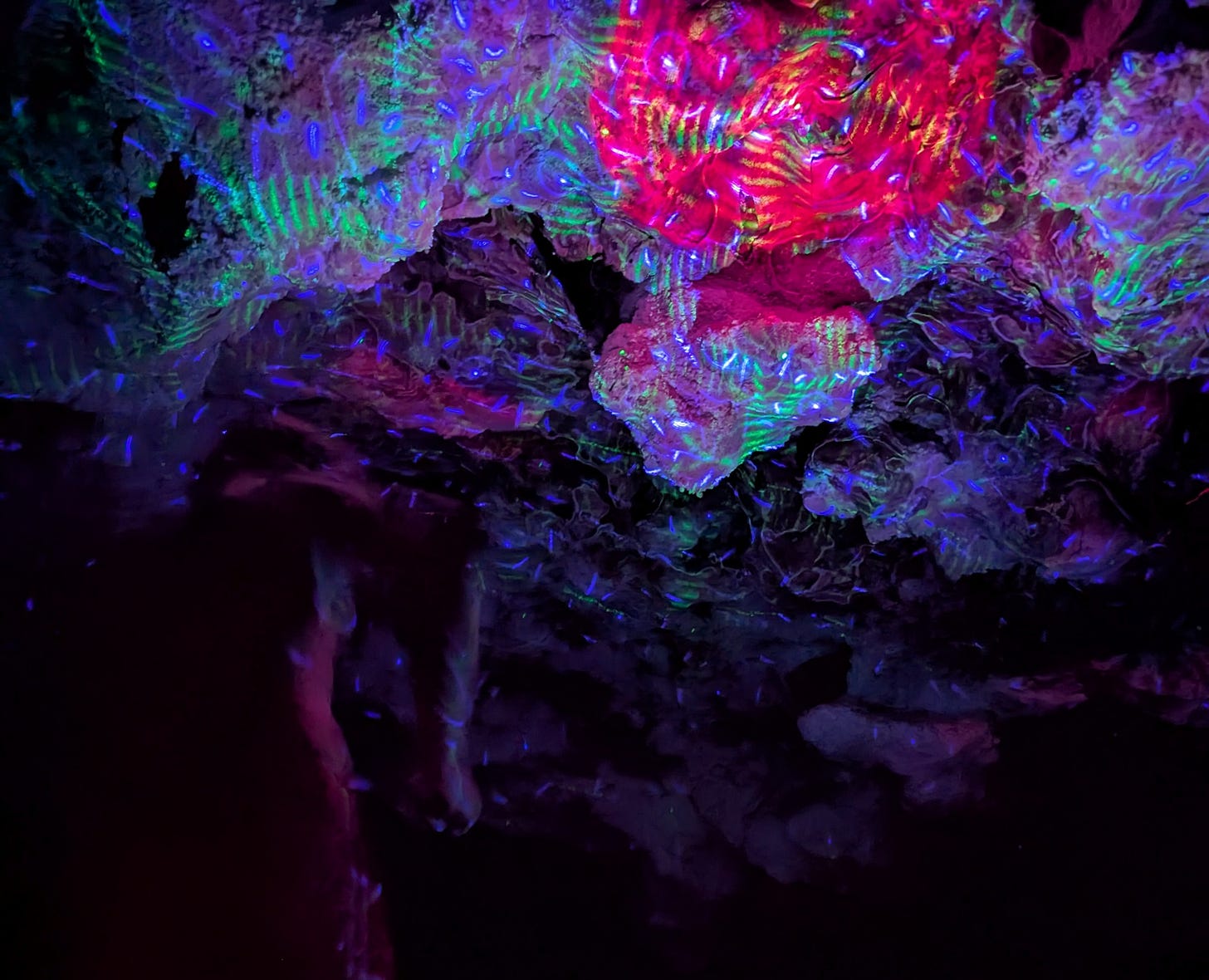

At camp, we had a pleasant surprise waiting for us: the other team had a laser light show going on the ceiling above camp, that they were all mesmerized by as they lied down on the Dude Bro Camp Spot below the illuminated ceiling. Garrett brought this compact, lightweight laser light show generator he got on Amazon into the cave, and it was so worth it!

The others at camp were pleasantly surprised to hear that we replaced all the ropes in the Kansas Twister and hauled all the old ones back, with the exception of the bottom rope because we couldn’t access the buried anchor. They weren’t sure if we were going to be able to get it all done in one day. We sure did, while doing lots of sightseeing too!Hunter and Garrett and Karla’s team had some objectives that included going to the Far Western Camp to assess it for reopening (I’m not sure why it was ever closed), going to Oasis, Red Lakes (or maybe it was Red Seas or Red Tides, one of those), and assessing some of the abandoned science stations there. Their trip went well, although I confess to not knowing the exact details. Hunter took some amazing photographs that blew me away. I’ll put one here because it’s astounding, but I won’t share all the good ones because I wasn’t there. Check out Hunter's Facebook post for all his best pictures.

After some time spent passively admiring the laser light show while making dinner, it was time to party. Georgia broke out the speaker she hauled in to camp, and the party was started! We all danced under the lights and enjoyed the scenery and the satisfaction of a job well done. The heat stopped me from dancing a few times, and I just layed down staring at the ceiling before cooling off enough to continue boogying. It was definitely the most fun I’ve ever had at cave camp. It’s nice when your camp is warm and spacious and flat and you can lounge around and hang out and party!

We went to bed around 4am. Totally worth it for the long, fun day and the good times at camp.

Monday, May 26th

Today was our day to leave for the surface. Although Hunter set his alarm for 11am, everyone was up before then, either naturally or from the sound of the others packing. Getting ready to leave and packing up camp took a while, as it was 1:35pm before everyone was gone from camp and moving towards the entrance.

My pack was a fair bit lighter than on the way in. We did have collectively ~150 ft less rope than we carried on the way in, due to leaving the 100 ft new rope at the pitch where I couldn’t access the buried anchor and 50 ft of old rope at the spot in the Kansas Twister that I thought wanted a traverse line. But the old rope was damp and dirty, which made it heavier per foot than the new rope. I also had much less food, although I had two mornings worth of poop to carry out. That always weighs more than you think, often more than the food it was made from, because it’s hydrated, unlike dried camp food. The biggest weight reduction was from me carrying two liters of water out instead of the 6.5 I carried in. That alone saved nine pounds. With the liter I had stashed on the way out in various places and the half liter I had at the entrance, that should be plenty. I crushed the 3.5 liter plastic jug of water to save space and only carried water in my two Nalgenes. My pack was also a little less unwieldy and snaggy, as I only had one rope tied to the outside, and the rest stuffed into the bag. I had something like 250 ft of old rope on the way out, less than the 390 ft of rope I carried in.

We would cave out in two teams: Georgia, Michael, and I would go first, and Hunter, Garrett, and Karla would go behind us. Caving in smaller groups would be nice to prevent traffic jams on rope, although that wasn’t a huge deal here as there was only one really long rope, Boulder Falls. And our team didn’t stay exactly together on the way out; we all separated and caved at our own pace, although I waited for them at the bottom of the Great White Way and at EF Junction.

The way out has more hiking up steep breakdown slopes than any other caving on the trip so far, so I was eagerly awaiting that to see if that heat did me in. While I was certainly plenty hot the whole time, I felt very manageably hot, not like I was overheating. Overall, I was pleasantly surprised with how I managed my temperature this trip. That was what I was most nervous about (really, the only thing I was nervous about) going into the trip, and it was fine. I didn’t even get the forearm cramps that I often do when climbing rope in a hot sweaty cave. I think that’s because I made it a point to eat tons of salt on this trip. The spicy dried mangoes I brought were very salty with Tajin, and I also ate a bunch of straight salt in the form of bouillon cubes, those dried blocks of soup broth that are actually just mostly salt, but flavorful salt that’s edible in large quantities.

I didn’t notice the sudden temperature change above Glacier Bay near the bottom of Boulder Falls, probably because I was exerting myself more and just maximally hot the whole time. When I got to Boulder Falls, I took a few minutes to cool off and drink the half liter of water I had stashed there before the big climb up. I allowed myself a few stops on rope to take it all in and look around the huge chamber I was suspended in the middle of. I got to the top right as I heard Georgia and Michael approach from below: perfect timing.

Although I did not notice a sudden temperature change around Boulder Falls, it was definitely there, because waiting at the top of Boulder Falls was the only time the whole trip where I got cold. I still had no clothes except short shorts then, and I stopped to wait for the others for a while. When Georgia got to the top I announced I was heading out of the cave, as I was actually chilly. It was probably about 60 degrees.

It’s only about 20 minutes to the entrance from there. One of the short ropes between Boulder Falls and the entrance (the one on a low-angle flowstone slope below the Liberty Bell room) is coreshot, tied off with a butterfly, and awkwardly shortened in a way that pulls you off to the side of a slippery flowstone slope. That spot could use some bolts to anchor the rope in a better place, maybe.

At the entrance pit, my chest was chafing pretty bad from my chest harness. Thankfully that was the only time it really affected me—on the last pit of the trip. Although if it hit earlier in the trip, I could have just put on a shirt. I think next time I’ll try climbing rope with a crop top—something to protect my chest from chafing against the chest harness, but with maximum ventilation.

I was on the surface around 5:30pm. I waited for a while for Georgia and Michael, while chugging water and enjoying the sunshine. It was buggy out, which is rare for the Guads. That and the fact that the plants looked extra green and all the cacti were blooming made me think it must have rained while we were in there. It was warm and sunny, but not hot at that time in the late afternoon. A comfortable temperature to lounge around on the surface and sunbathe.

Our team, Georgia and Michael and I, started hiking back right as Karla got to the entrance. We said goodbye, then ditched them, as I had work the next morning and didn’t want to wait much longer to start driving back. Although I did stop to get some Taco Bell with the three of us after the trip. How could you not do a post-caving meal together! Thanks Michael for getting us all TBell.

The drive back to Albuquerque was long, and especially tedious because I didn’t have my phone to play music. My phone mysteriously bricked itself in the cave, which is why I don’t have too many pictures in this post. Maybe the humidity caused water damage? I listened to the radio the entire drive home, which was terrible. I am totally addicted to Spotify.

Anyways, it was a super fun trip in an awesome cave, and I can’t wait to go back. There’s more work and exploration to do in Lechuguilla! Thanks to everyone who was on the trip and made it happen.

As God herself intended.

Because Lechuguilla has no running water nor flooding, you don’t pee in the cave. For one- and two-day trips, you carry out all your pee. For three-day trips and longer, there is a designated sacrifice spot at each camp where you can dump your pee. So you carry all your pee back to camp each day, and dump it in the one spot, at the very end of the week before you leave so the smell doesn’t stink up camp the whole time you’re there.

Another great trip report in an amazing cave with some awesome people!

Thanks for the detailed and interesting trip report! I'm not sure I'll ever be able to go to Lechuguilla but it sounds amazing and I can at least imagine it based on your descriptions. And that sounds like a really fun group to cave with, I heard a bit about this trip from Mike and Karla at the Sandia grotto meeting.