Prince of Wales Island, Alaska 2024 caving trip

2 weeks of caving in the rainforest

This past summer, I escaped Albuquerque for a month long caving trip, July 6 to August 4. The first 2 weeks I spent on Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska, and the second 2 weeks I spent at Tears of the Turtle Cave in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana. This post is about all that I got up to for those first 2 weeks in Alaska: first, a bigger organized trip the first week with 12 people (Reilly Blackwell, Ian Clarke, Christian DeCelle, John Dunham, Amelia Fatykhova, Anna Harris, Jared Higgins, Hannah Keith, Michael Ketzner, Alex Lyles, Gooseberry Peter, and myself. Then a smaller, less organized week of caving the second week, with just Christian, Reilly, Michael and myself.

Prince of Wales Island is a large island (larger than Delaware) off the coast of Alaska, at the southern tip of its panhandle. It is a lush, wet, green temperate rainforest, not unlike the rainforests of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington. Not full of barren snow-capped mountains as many people imagine when they think of Alaska. To get there, you first fly into Ketchikan, Alaska, a small city on Revillagigedo Island, adjacent to Prince of Wales. Plenty of flights there from Seattle. Then you take a 3.5 hour ferry ride from Ketchikan to Prince of Wales Island, operated once a day every day by the state of Alaska's Inter-Island Ferry Authority. Technically you also have to take a short (5 minute) ferry ride from the Ketchikan airport to Ketchikan itself, as the airport is on a tiny island right next to Revillagigedo Island.

I flew to Ketchikan on Saturday, July 6, intending to stay in a hotel in Ketchikan with fellow team members Amelia Fatykhova and John Dunham before taking the Ferry to Prince of Wales the next day. And then began the first of several minor mishaps that happened on this trip: Alaska/American airlines lost my checked bag! This was particularly bad because once we took the ferry from Ketchikan to Prince of Wales Island the next day, we were planning on driving several hours from the ferry terminal (where we could pick up the bag if/when it arrived) to where we would start our approach to the caves, and then hike several hours up a mountain to setup basecamp. So it would be infeasible to go all the way back to the ferry terminal to get the bag midweek. Additionally, we would have no cell service to get notified if/when they found my bag. So I was worried about being stuck in limbo without my essential caving gear all week.

Thankfully, American Airlines found it the next morning, Sunday July 7 (stuck in Phoenix, where I had a layover). They flew it to Seattle then Ketchikan, although it was scheduled to arrive in Ketchikan after I was to board the ferry to Prince of Wales at 3 pm, so I would be unable to pick up the bag before leaving. Thankfully, Alaska Airlines, which was in custody of the bag at this point, said they could send it over to Prince of Wales Island via Island Air, a small local airline that operates seaplane flights between Ketchikan and Prince of Wales Island. However, there was still the problem that the bag would arrive on the Island Air flight in Klawock, AK, on Prince of Wales Island, on the last flight of the day, shortly before the airline closed at 7 pm. We wouldn't be able to get from the ferry to Klawock until after 7 pm. Klawock was 2.5 hours from where we planned on driving to and sleeping that night, and we really didn't want to have to drive back the next morning, when we were supposed to be backpacking up to basecamp. After several calls to Island Air, I convinced them to leave my bag outside, hidden away in a corner, so I could pick it up that evening after they closed on the way on our drive from the ferry terminal to where we were staying that night.

That all worked, and I retrieved my bag and all of us that took the ferry started the 3 hour drive from Hollis, where the ferry terminal is, to the El Capitan Cave guide cabin, where we would all be spending the night. Anna and Christian, US Forest Service employees who live on Prince of Wales Island and make this trip happen, picked us up and transported us and all of our gear in Forest Service vehicles, and arranged for us to stay at the guide cabin that the Forest Service has at El Cap Cave. This is part of the incredible amount of support we get from the Forest Service for these trips. The Tongass National Forest is very interested in knowing about the caves on its land, and supports our cave exploration and mapping efforts in exchange for locations and data for all the caves we find and explore.

That night we stayed at the guide cabin for El Capitan Cave, a cave right by the ocean where the Forest Service offers tours to the public. Every summer they hire 2 interns to be tour guides, and they live at that cabin all summer. They had that week off so that we could stay at the cabin, although they were still there when we got there and stuck around for a while to hang out. Living in a cabin in the middle of nowhere, far from any town, with only 1 other person as your human interaction most days, must get lonely, and thus they seemed eager to hang out and chat.

Monday, July 8

The next morning, Monday July 8, was our day to backpack up to basecamp, setup camp, and start caving. We ate a luxurious breakfast of eggs and salmon that Anna caught before driving a short ways from the guide cabin to where we would start our hike up to basecamp. Thankfully it was dry and sunny that day, not rainy as it usually is and as it was supposed to be the rest of the week, which meant that we could setup camp without getting all of our stuff wet. The hike up to basecamp started out on an old overgrown logging road, which the Forest Service fire crew on the island had recently helped clear a bit, before going off trail and up a steep hillside. We all got quite hot while bushwhacking up the steep hillside with the sun out, but we knew this relatively pleasant weather wouldn't last so we didn't complain. After about 2 miles and 1200 ft of elevation gain, we arrived at basecamp, which was a huge (~500 ft wide), open, grassy sinkhole enclosed by rocky mountains and a sparse pine forest rising above camp, a bit north of El Capitan Peak. Serene.

Me and Christian led the hike up and got there shortly after 11am, not quite 2 hours after we started hiking. We met Anna and Alex Lyles at basecamp, who had already hiked up a day earlier. We took a few hours to setup our tents and make some food before setting off to go caving that day. The forest service paid for a helicopter (!!!) to fly up much of the group caving gear such as rope, bolts, and drills, and all of our food, so base camp was fully stocked when we got there without us having to carry super heavy bags. The kitchen area had a nice large folding table we could use to prep food, and a Coleman stove, so it would be no issue boiling water for 12 people's meals. It was covered with large, standing-height tarps, so we could all hang out and be dry in the kitchen. We also had an battery-powered electric bear fence that enclosed the 10 ft by 20 ft kitchen area, so we wouldn't have to bear hang our food at nights. There are no grizzly bears on Prince of Wales Island (thankfully), but there are black bears that will mess with your food if you don't store it properly. It was a nice convenience not having to deal with any bear hangs, especially since we had tons of food for 12 people for a week and it would have been a pain to hang it all up and take it all down twice a day.

After setting up our camps, we started getting ready for a half day of caving that day. That entailed packing up some gear, namely rope, bolts, a drill, among other things, all of which the Forest Service had helicoptered up to basecamp. I also taped up my big toes, because they had developed some rub spots due to hiking up to basecamp in my rain boots. I tried that somewhat bold strategy of using my rain boots, or wellies as cavers call them, as my hiking shoes in addition to my caving shoes, to save weight and to save the inconvenience of having soaking wet hiking shoes after it started raining on the surface, which it surely would. However, my wellies abraded my big (and later, little) toes pretty bad, and I had to tape them up to reduce the sensitivity of the rub spots.

For the 4 teams we had up there, we had 3 Milwaukee M12 drills (which are small, lightweight drills that drill pretty slowly but are easy to pack and carry far) and one Bosch 36V (which is the opposite—large, heavy, but drills like a champ). Naturally, I wanted our team to take the 36V since we had a lot of bolts to place, and I love carrying heavy things anyways. The lead our team selected to work on was in -560 ft in Snowhole Cave, a known cave, 652 ft deep, that had last been visited by Kevin Allred, Mark Fritzke, and Pete Smith in 2010. They left off a wide open pit lead marked on the map as "unexplored pit about 70 ft deep, with murmuring water sounds from below". What an excellent lead! But, to get to that lead at -560 ft in Snowhole, we figured we would have to do lots of rigging which would probably entail placing a bunch of bolts. The previous crew who had been to Snowhole used more natural anchors and used much fewer bolts, preferring to use thicker, stiffer ropes and rope pads so the ropes could stand up to the wear and tear resulting from rigging that is less bolt-intensive and less impactful to the cave. Cavers call this style of rigging "indestructible rope technique" (IRT). The rigging style we preferred is what cavers call "alpine style"—carefully rigging ropes so they stay away from the cave walls and don't abrade. This lets you get away with much thinner, lighter weight rope, and is generally more suitable for long-term rigging, although it means you have to place more bolts and thus impact the cave more. Anyways, we took the 36V drill because we figured our team had the most bolts to place, and because no one else wanted to carry it.

Our team, which was Christian, Reilly, and myself, left camp at 3 pm and set off for the cave. We had a GPS point from the last crew that went there, which was only 20 minutes from camp. The approach started out in the sparse pine forest above the grassy sinkhole that was camp before breaking out into some impressive karst terrain above the trees. The karst was steep exposed limestone pavement, largely very smooth and monolithic, but punctuated by gaping earth cracks and razor-sharp rillenkarren (prominent solutional channels carved into steep surfaces on the limestone).

The approach hike to the GPS point we had for Snowhole was short, scenic, and pleasant; the only problem was there was no cave when we got there. We spent about 2 hours looking around, wandering in concentric circles around the GPS point, hoping it would be not far off what we were told. We were told the entrance was a 2 ft by 50 ft long crack in the earth, so we figured there's no way we would miss it if we walked over it. After doing enough concentric circles for me to be sure that this was futile, we stopped and thought about what to do next. Thankfully Christian realized he had some old cave documents downloaded on his phone (no cell service up here) that had some info about Snowhole. One of the documents had a location that was different from the GPS pin we had (which was from the Forest Service database of caves). That location was not far away and turned out to be the cave entrance. Probably the location we had from the Forest Service was an estimate from the pre-GPS era—hand drawn on a topo map, then entered into a database of GPS points without noting that it was a rough approximation of the location.

We brought all our gear, which we had ditched at the wrong GPS point when we started doing concentric circles, over to the entrance. It was exactly as described: a 2 ft wide crack that ran up a slope for about 50 ft. It's the type of feature that you would often ignore when out ridgewalking, as these earth cracks rarely go. And apparently many cavers did ignore it over the years—for many years people just stepped over the crack on the approach to Blowing in the Wind Cave. Until one day someone decided to drop some rocks down it to see what they did, and they head the rocks tumble for quite a ways. Then they realized this crack was actually a cave and started exploring it.

When gearing up at the entrance, I realized that my helmet had a big crack in the foam. I'm pretty sure I cracked it by stuffing it into an overhead compartment on a plane, as this crack was not there the last time I caved with it. Helmets with some exposed foam, and a hard plastic shell only over the top of the helmet, are a fairly lightweight style of helmet and questionably durable enough for caving. I had used this helmet for plenty of harsh caving and hadn't noticed any issues with the foam, then of course broke it not from caving but from flying with it. Not good! I needed to use this helmet for the next month, including at Tears of the Turtle Cave, which is notorious for destroying gear. I would see what repairs I could do when back at basecamp, but for now I would just have to use the cracked helmet and try not to make it worse by bashing or dragging my head against a wall.

It was just before 6 pm by the time I was ready to go in the cave. The plan was for me to go down with all our rope and the drill and bolting stuff, and rig down as far as I could in a few hours. The map showed the cave going pretty much straight down one pit complex until -450 ft, perhaps with some small landings which may or may not fit multiple people. I wasn't expecting to get to the good flat area at -450 ft in one day, so Christian and Reilly would follow only if I got to a good spot for multiple people to hang out and get off rope, otherwise they would just hang out on the surface waiting for me to call to them. There were no options for natural anchors on the surface, so I put in 2 bolts to start a lead-in line to the entrance. I put in a rebelay right below the lip, another partway down the crack, and a redirect before getting to a small ledge with some snow where I saw a rebelay bolt from previous parties, the first so far. I could tell that previous parties were definitely rigging this IRT-style. I backed up the single bolt with another at that rebelay ledge, and continued down the pit. Here the pit changed shape from a long skinny earth crack to a more classic circular cross section pit; it now looked like I was in a real cave, not an earth crack. I set another rebelay at another sloping snowy ledge before deciding it was about time to head back up to the surface. I had killed lots of time trundling loose rocks from the walls of the pit to remove rockfall danger on my way down. The walls of the pit were generally good hard bedrock, but clearly the pit had collected a lot of small-medium rocks and other debris over the years, much of which was precariously perched in various nooks in the crannies in the walls, waiting for the slightest disturbance from a caver's foot or swinging cave bag to knock it loose and send it crashing down on whoever was unlucky enough to be below. I wanted all of that debris gone before anyone else came into the cave, and it took quite a bit of effort trundling everything that looked remotely dangerous.

I packed up the drill in a dry bag, and hung it and the rest of the rope and bolts (I had used 11 so far—2 for a lead-in line at the entrance, 4 2-bolt rebelays, and a redirect) at the last rebelay I set before heading back up to the surface. I got to the surface at 8:30 pm, where Christian and Reilly were sunbathing on the rock, enjoying the last bits of warm sunny weather before the rain was supposed to roll in. From looking at the map, I guessed that I got to around -200 ft that day, although the map has very little detail in the entrance series so it was hard to tell. We found a super easy route down from the cave and made it back to camp in a mere 17 minutes. We made dinner at our luxurious camp kitchen and were in bed by 11 pm.

Dinner that night, as with every night, was rehydrated Dinner Mix—a lightweight and calorie-dense mix of dehydrated food ingredients that you only have to add hot water to in order to make it into a hot meal. I was in charge of acquiring all the food for everyone on the trip. Naturally, I, a physicist, was much more concerned with things like energy-density, nutrition, ease of cooking, and cost-effectiveness of the food rather than aesthetic factors such as the food tasting good or not eating the same thing every meal. So I decided to just order a bunch of dinner mix ingredients in bulk. I first found out about dinner mix as cave food when I went on the Cueva Cheve expedition in Mexico in 2022; dinner mix is standard cave food there too. The dinner mix I make is somewhat modified from the Cheve mix, but the idea is the same. The ingredients that go in the dry mix are:

Instant mashed potatoes powder

Chia seeds

Cashews

Walnuts

Textured vegetable protein

To turn it into a meal, you add boiling water and some butter and let it rehydrate for just a few minutes. The powder absorbs all the water and expands a bunch and turns into a filling hot meal. The nuts provide a nice crunch, so the texture is not just slop. We did have some add-ins that people could use to spruce up their meals, including cheese, sun-dried tomatoes, bouillon cubes, and various spice blends. Once you add in a few of those, dinner mix can actually be quite good, and everyone on the trip seemed to like it, at least enough to not get sick of it after eating it for every dinner and breakfast for a week. I even had a few people ask me for the recipe so they can make it for themselves.

The big advantage of dinner mix over what we had done in previous years (trying to cook normal meals, and designating one team per night to be the cook team) is that anyone can easily and quickly cook a full meal, whenever they want, in whatever quantity they want, without relying on anyone else. In previous years, one team would have to get back to camp early to cook dinner, which would mean they would have a shorter day of caving. They would inevitably make too little or too much, and when other teams would get back from long days at strange hours in the middle of the night, they come back to cold food, if there was any left at all. Dinner mix solved those problems. It also had the big advantage that all the ingredients could be purchased in bulk on Amazon and shipped to Prince of Wales Island (Amazon Prime works there!). No need to pay expensive Alaska prices. For lunch/snacks during the day, I bought fairly standard cave fare in bulk—cheese, tortillas, nuts and seeds, dried fruit, chocolate, and some other candy. The only things we had to buy on the island instead of online in bulk were the cheese and butter. The food situation worked great, and I plan on doing more-or-less the same food plan next year. All of the food was helicoptered up to basecamp by the Forest Service.

One ominous note: this day, Michael Ketzner started feeling sick. The week before, he had been at the NSS convention (national convention for caving in the US), where apparently COVID was running around rampant. Could Michael be spreading COVID to all of us? Oh well, not worth worrying about it now that we had already spent a bunch of time together…

Tuesday, July 9

The next day, Tuesday July 9, the sun woke me up at 7 am. Before everyone else got up, I took some time to do a few miscellaneous tasks around camp. I dug a deep latrine so people wouldn't have to dig their own cat holes every day. I also flagged a trail to it from camp so people could find it easily even when stumbling around in the dark at night. Then I repaired my flip flops (useful for walking around camp), which I had accidentally torn some of the straps on the day before. I brought a speedy stitcher, a tool that lets you sew with heavy-duty thread into thick fabric, up to camp as an emergency repair tool, and I'm glad I did because I already needed to use it by day 2. With the speedy stitcher and some 1" webbing we had at camp for redirects, I was able to re-attach the torn flip-flop straps.

After a hearty breakfast of (you guessed it) dinner mix, we were out of camp by 10:30 am and at the cave in a short 20 minutes, carrying even more rope and bolts that we brought the previous day. I told Christian and Reilly (who were my teammates the entire week) to give me an hour and a half head start while I continue rigging, figuring that I would get to a landing marked on the map at -328 ft before they caught up to me. 2 more rebelays and 2 more redirects got me to that landing, which was a 3 ft by 8 ft ledge where you can get off rope and 3 people can fit. The timing worked out nicely, as Christian and Reilly caught up to me there as I was rigging the next pit that continues down from the edge of the landing. That pit had a short pitch with a tight awkward entry to a rebelay, then a long pitch that starts out in a tight crack where I put in 2 redirects and turns into a huge circular cross section pit, then another short pitch that I put in 2 bolts for although we ended up just free that last short pitch. Here we finally gained a waterfall which lightly sprays you as you descend the big part of the long pitch, the first flowing water in the cave.

Now we were at a fairly large flat area at the bottom of the pit with a flowing stream in the floor, with the passage continuing horizontally to the south and rapidly narrowing. We were pretty sure that we were at the spot on the map at -485 ft immediately before "The Stripper", a tight vertical squeeze we had been warned about. The passage continuing south exactly matched that description: continuing tight, then getting even tighter as it steepens and you want a rope right before the lip of the larger steeper pit visible beyond. I rigged a rope through the squeeze, struggled moderately down it, and was quickly beyond the squeeze into a nicer, bigger pit. I shouted triumphantly to Christian and Reilly that The Stripper wasn't even that bad.

After The Stripper, the map indicated that I was supposed to not go all the way to the bottom of the pit, but instead find a window into some horizontal passage heading north. I did indeed find such a window, but it was extremely tight, and I was surprised that The Stripper would be labelled on the map but this tight, nasty-looking window heading north would not be named something worse. I got into it, set 2 bolts to get the rope in the right spot at the window, and started squeezing down it. I realized this couldn't be the way on when I saw fragile, easily broken protrusions in the rock right at the widest spot where people would go. Surely if anyone had been down there, they would have broken them off. This must not be the window.

I derigged the rope from that window and went down to the bottom of the pit just to check it out. It was not plugged with rocks as the map indicated; instead I saw survey stations continuing down a tight passage that also visibly constricted right at the lip of a pit. I realized that we had not yet gone through The Stripper—I was staring at it right now. The ledge we landed on previously was actually the ledge on the map at -450 ft, not the ledge before The Stripper at -485 ft. Now we were actually at -485 ft.

OK, so now it was time to face down The Stripper. I bolted an anchor right at the start of the tight part of the passage to get the rope in the right spot, and rappelled down it. Really I rappelled sideways through it, thru passage that you wouldn't even want a rope for if there weren't a pit right at the other end that you can't see because it's so tight. It was slightly trickier than the previous squeeze, but not that much worse. It was a little less pleasant because the stream ran thru the floor that you push your arm and leg off of, so that arm and leg do get quite wet.

Now that I was actually thru The Stripper, I saw an obvious window in the wall of the pit that continued to the north as hands-and-knees crawling horizontal passage. This was clearly the window that we were supposed to find. I rappelled to the level of the horizontal passage, swung into it (in the process swinging myself right into the waterfall going down the pit, getting myself even more soaked than I was after going thru The Stripper), and mantled into the hands-and-knees crawl passage. I crawled a bit on the breakdown floor to a comfy spot then anchored the other end of the rope there, so the others would not have to repeat the tricky mantle move I did to get into the window. There were 2 interesting and surprising features of this passage that I noticed as soon as I got into it. First, the passage had ridiculous air moving through it. The cave was sucking here, in contrast to the entrance which blew a much smaller amount of air. Not the best thing to run into when you're soaking wet, but I didn't mind that much because all this air was very promising. Airflow is generally a good sign that a cave is going to keep going—in fact, there's a common saying in caving "if it blows, it goes".

The second interesting feature that I noticed was that the ceiling was a flat bedrock layer that was distinctly different from the limestone the cave was formed in—probably an insoluble shale layer. The fact that the ceiling, rather than the floor, was an insoluble layer means that this passage likely formed by water being pushed upwards from below, running into the insoluble layer which stops upwards progress of the water and forms a ceiling. This is in contrast to what more often happens when caves form: water flows downwards, stopping at insoluble layers that stop downward progress and form a floors. What would cause water to be pushed upwards like this? Probably this entire section of cave was flooded, underneath some sort of water table, and the high pressure from deep water forced the water to flow in which ever direction is could find weaknesses in the rock, which could be any direction, up down or sideways. When cave passages forms this way, fully submerged in water, we call such passage "phreatic". Cave passages that form not submerged bur rather at or above the level of the water table are called "vadose". We don't see much phreatic passage in Alaska caves, so we were all excited to see where this one would go and what it would do.

We followed this passage for a few minutes of hands-and-knees crawling, excitedly power-crawling as the strong air egged us on. The dirt in the floor of the passage was bone dry, thanks to the air ripping thru the passage, and we were able to dry out our soaking wet suits by dragging them along the dirt, which was nice. The next obstacle a few minutes down this passage was a large pit in the floor that the crawlway spilled out into. The pit was about 20 ft in diameter, and deep enough that we couldn't see the bottom. A traverse rope was anchored to our side of the pit with one bolt and continued out of sight around a corner where it appeared that the crawlway continued on the other side of the pit. There were also several short ropes stashed here by the previous team, which was convenient for us because we were low on rope at that time. We had no qualms taking the rope, because the last team that had been here left them here 14 years ago and had no plans to come back. We backed up the 1-bolt anchor with a new bolt we placed, and I went first across the traverse rope. Because I didn't know what it was anchored to on the other side, I put an ascender on the traverse line, facing the 2-bolt anchor on our side, so that if the anchor on the other side failed, my ascender should catch me.

The rope was anchored to a huge boulder on the other side: totally bomber. I told Christian and Reilly that the anchor on the other side was good and they didn't need to use an ascender on the traverse line for safety. We all got across and continued along the crawlway on the other side. Notably, the crawlway lost almost all of the airflow at the pit; it was very faint on the other side. The air must be going down the pit or down one of the other passages connected to the top of the pit that aren't the 2 passages on both ends of the traverse rope. There was a good-looking horizontal passage at the same height of the traverse rope on the other side, making the top of the pit a 3-way intersection. Later we looked at the map and saw that they did get to that passage, and that it went for about 100 ft before ending at a spot labelled "crack too tight, takes air".

Despite being slightly disappointed at losing the air, we continued down the crawlway on the other side of the pit going towards our lead. The next obstacle was a small downclimb and slope labelled "slick mud, rope needed". When I got there, I went down it then back up, and found it doable without a rope but certainly agreed that a rope there would be helpful. We used one of the short ropes we found stashed at the pit traverse. Because it was an old stiff 11 mm rope, I used a somewhat creative and funny way to attach the rope to a bolt: rope straight through the bolt hanger and a barrel knot on the other side of the hanger. This is very efficient as it uses very little rope and no quicklink. It's totally safe because we were using Pingo Bonier hangers with very round edges that let you tie the rope straight to the hanger, and because we were using old swollen 11 mm rope that would never pull through the bolt hanger hole. It's just a very unconventional way to rig.

Just beyond this chimney downclimb then mud slope was our lead: a wide open pit with a large, comfy, walking-height room where we would get on rope. The final station from the last push trip 14 years ago, E48, was clearly labelled on a wall right where you would want to get on rope. Throwing rocks down the pit and timing them was consistent with a depth of about 70 ft, and we could hear water below, just like the lead was labelled on the map: "unexplored pit about 70 ft deep with murmuring water sounds below". Time to start some new exploration, woohoo! We As Christian and Reilly stopped to unpack and switch gears to survey mode (I was to continue rigging), I was dismayed to find out that I only had 2 bolts left. It was only 6 pm, and we were in no rush to get out early, so I had to be stingy with the bolts. A change from how I had been using them the past 2 days: rigging everything as perfectly alpine as I could, eliminating any and all rope rub. Oh well, at least the next day we would return with many more bolts and fix whatever MacGyver-rigging I was about to do.

We all looked around for natural anchor options, hoping to save the bolts for whatever came next. We didn't find anything bomber; one small horn I considered shattered when I hit it with a hammer, so that was definitely out as a natural anchor option. I decided to place the last of the 2 bolts we had right at E48 and just roll with it, hoping that we would make it to the bottom of this pit without excessive rope rub. Indeed the rope rub was not bad: the lip of the pit was mud, which meant that chunks of mud did fall down on you as you were on rope below the lip which was annoying, but I wasn't concerned about excessive rope wear from just one party going down then back up the rope.

Christian went first down the rope, because then I had to poop (thankfully there was a large muddy area away from where we walk there, so I could bury it and not pack it out). After we all got down the pit (which was in fact about 70 ft), we started surveying down a crawlway at the bottom. This crawlway was muddy and had no air and no water, so it didn't seem super promising, but after only a few shots we got to a standup room where there was another pit! We were out of bolts at this point, but thankfully there was a large boulder we could tie the rope around. I went down this pit first. The IRT rigging around the boulder was not ideal—it rubbed badly over multiple edges, and it put you right in the path of the waterfall (the passage picked up water right before the pit). We would have to fix this when we returned the next day. But, it was good enough for me and Christian to get down about 40 ft to a large comfy ledge where we could get off rope. Reilly didn't come down then because the rigging sucked and we were gonna come back the next day anyways and do it with better rigging. We got the survey down to that ledge, beyond which the pit continued down as 5 ft wide, very tall canyon, with no floor visible below. We would need bolts to go any further. A great lead to return to the next day!

One more thing we had to do before gunning for the surface was tie in the bottom of the first new pit from that day with E48, as we started the survey at the bottom of that pit. We did that in a few shots, left the drill and remnants of our bolting supplies (8 quicklinks, 3 bolt hangers, no bolts) at E48, and bolted for the surface. I started exiting from E48 around 8:45 pm and made it to the surface just before 10 pm. While ascending out of the cave I noticed myself coughing a bit—was I getting whatever sickness, possibly COVID, that Michael had? I wasn't too concerned at that moment because my sickness seemed pretty mild. It didn't hold me back while caving hard in the cold all day.

When I got to the surface it was cool out and lightly raining, so I hiked back in my cave suit, which saved some trouble over changing out of my cave clothes as the conditions mandated I do the previous day. I was in bed just before midnight.

Wednesday, July 10

We woke up this morning eager to return to where we ran out of rope the day before: at a wide open pit dropping down into a tall canyon that meandered around a corner out of sight. All night that canyon was calling our names, beckoning us to follow it around the next corner and see where it would go. Reilly had a job interview (via Zoom) that morning, so the plan was for me and Christian to head into the cave in the morning without Reilly, and she would join us when her interview was done. Thankfully she could get cell service by scrambling up the hill to a high point above camp and above all the caves. Quite the place to conduct a job interview—atop a rocky hill overlooking the ocean in the backcountry of an Alaskan island.

Reilly left camp early to get to her high point while me and Christian took our time, only getting out of camp at 11 am and into the cave around noon. Part of slowed us down was that is started raining that morning, so we were naturally reluctant to leave our comfy tarp city that was the camp kitchen and get out into the rain. We all hoped that Reilly was handling her interview OK while sitting out in the rain (I later learned that she got the job, so she did in fact handle it OK!). We stopped before the lead where we turned around yesterday to fix the substandard rigging we did the day before after running out of bolts. This took longer than I thought due to some awkward, muddy, precarious positions I had to drill from, but after a few hours I made the rigging on all the new drops nice and freehanging. After making it to our deep point from the previous day, I forged ahead with the drill and rigging supplies while Christian and Reilly (who had made it into the cave and caught up with us) continued the survey behind me.

One more drop from the ledge where we turned around the day before brought us to a nice walking canyon, 4-5 ft wide and taller than you could see. The floor was a mix of bedrock and small breakdown that made for nice pleasant walking. One nuisance drop in this canyon and a short bit of walking brought me to the next substantial drop, at which the cave changed significantly and made the rigging more complicated and tricky.

At this drop (F12), the cave walls picked up a thick mud layer. I was able to scrape some mud off one of the walls right before the pit and get in 2 good bolts for a lead in line. But all the rock after the lip of the pit was terrible—I would hit it and it would either reverberate with that bongo-drum sound that tells you to stay away, or crumble under the force of the hammer. The lip was smooth enough that we probably could have IRT'd this drop without damaging the rope; but there was quite a substantial stream at this point that made a waterfall down the pit, meaning you definitely could not just throw the rope and rappel down without getting yourself dangerously soaked in 38 degree water. So I absolutely needed to find good rock for a rebelay to keep the rope (and caver) out of the waterfall.

After testing all of the rock remotely near the lip of the pit, I found a patch of good rock awkwardly off to the side that I could get 2 good bolts in. This rebelay was far enough away from the water, but it would not make the rope freehanging. Thankfully we still had some beefy 11 mm rope we could use for this non-freehanging drop. It was quite awkward and strenuous drilling way out to the side of the pit entry, and required my putting in a traverse line to access the anchor from back before the lip, but I got it done and it allowed us to get down this drop without getting soaked.

Probably this explanation of the strange geometry of this pit makes no sense without pictures, but we were all either too busy (me) or cold due to waiting around (Christian and Reilly) to bother to get good pictures of this pit. Here's one we got of Reilly trying not to freeze while I worked on this tricky drop.

After that awkward section you land on a breakdown ledge where you need another rebelay to make it down to flat ground where you can get off rope. Thankfully here there was an obvious spot with good rock for a rebelay that would make the rope freehanging and keep you out of the water (although the waterfall was lightly spraying me at this point, which was totally unavoidable). But before I could get in that rebelay, I had to trundle all the large and clearly unstable breakdown on that ledge. These blocks could easily be dislodged by someone swinging around on rope into one of them, or dragging a tethered pack across them, so they definitely had to go before anyone went any lower. This took a long time as I had to lift and move some pretty heavy rocks all by myself, sometimes while awkwardly hanging on rope. Christian and Reilly continued to shiver while I worked alone on this ledge. While I was trundling, something slightly scary happened I was standing on part of the ledge, hauling around various medium-sized rocks and chucking them off the ledge, while I was attached to the rope with some slack via a tied-off descender. All of a sudden the entire floor of the section of the ledge I was standing on (an area about 3ft by 3ft) collapsed and fell beneath me. I fell onto my tied-off descender, not far at all because I only had a few feet of slack, but it was still spooky. As I fell I swung around on the rope and got under the waterfall for a bit, getting pretty soaked. I stopped trundling a bit to calm down and collect my thoughts, as the unexpected (but very short and totally safe) fall had startled me. After my heart rate went back down, I continued trundling until the ledge was clear of dangerous blocks.

One more rebelay at an overhanging face just past the end of the edge brought me down to flat ground where I could get off rope and call for Christian and Michael to come back down. They had been waiting around for quite a long time while I trundled and rigged that tricky pit, and they were very cold. By this point all of us were coughing up a storm; we had clearly caught whatever sickness Michael brought. Being moderately sick certainly didn't make sitting around getting cold and wet any more fun.

The bottom of this pit was a decent-sized room, about 30 ft diameter, without an obvious best way on. The water poured into breakdown in the floor that seemed impassable. The floor sloped up into walls with interesting-looking holes in them. I scrambled up into one of them that didn't go (plugged with mud). I started scrambling up to another good-looking hole in the wall, but didn't like the slick mud slope guarding it, so I retreated. It seemed like just an infeeder anyways. Eventually I realized that the best way on was a small hole in the mud floor of the room, where the floor and walls met. There was a small gap between the mud floor and bedrock wall at one spot, about 1 ft tall and 2 ft wide, so too small for anyone to fit through, but with a larger void space visible beyond. I tossed some rocks down the hole to see what they would do—although they didn't go far or make any nice echoes, I could tell that the void space beyond the constriction was promising and worth digging into. It would be an easy dig, since I would just have to trench out the mud floor that formed the bottom half of the constriction.

I took all the rigging gear off my and removed my harness to get setup for digging at that hole. I also ate some food to warm up and fuel up for digging effort I was about to put in. By the time I was ready to start digging, Christian and Reilly had gotten the survey down to this room and were looking around, assessing all the nooks and crannies in the walls and floor to see if I missed anything. They too concluded that the best way on was this easy-looking dig at the hole in the mud.

We had no digging implements on us, but there were plenty of flat rocks around to use as shovels. I got to work shoving the sharp point of one of those rocks into the hard but malleable enough mud, scraping away a few inches at a time until I could fit down the hole. Eventually I got to the point where I wanted to be on rope to continue digging, as I was stuffing my legs down the sloping mud hole without seeing what was below me beyond a dark void space. Reilly set 2 bolts in a boulder right before the dig, and I got on rope to trench out the last part of the mud chute before declaring it big enough. I then rappelled down the mud chute, which was now about 2 ft high and 3 ft wide—certainly big enough for all of us to fit through, but still awkward, especially when carrying bulky things like the drill and a cave bag full of rope.

The mud chute went down into a little standing room about 4 ft in diameter. At the bottom of this room was another small hole in the mud with the sound of water audible below. This must be the water that disappeared into the breakdown before this mud dig. I scraped mud away from the sides of the hole, still on rope at this point, until I hit bedrock on all sides of the hole. There was still no way I would fit. Without specialized digging gear (which we had no desire to haul down here, let alone use for the hours it would take to widen this constriction), there would be no getting through to the stream below us. It seemed that this was not the way on, and that we would have to push other holes in the walls in the large room before the dig.

Ascending the rope back up the tight mud chute was difficult, as the concave nature of the lower surface of the chute meant the rope gut sucked into the mud which made it difficult to slide ascenders up the rope and make upward progress. After a little bit of wiggling and squirming, I made it out of the mud chute and told Christian and Reilly the news. Christian went in to solo survey to the end of the cave. After he came back out, he announced that he had gotten beyond the tight spot! Apparently I missed an opening that went horizontally across the top of that small standing room with the too-tight hole in the mud floor. Christian solo surveyed into that opening, which immediately opened up into a pit that he shot partway down, and got to just over 800 ft of depth for the cave. That made Snowhole Cave officially the deepest cave in Alaska, surpassing Vive Silva Cave at 797 ft deep. Woohoo! We now had at least one big success of the expedition.

We would be back tomorrow to rig down that pit and continue exploration in whatever was waiting for us at the bottom. But now, we were all cold and tired (and coughing up a storm from probably-COVID) and ready to leave. We ditched all the gear in the room before the dig and exited with near-empty packs. I got out in a little under 2 hours from near 800 ft deep. At The Stripper and the other tight spot just above it, I noticed that there was way more water than there was when we entered this morning. It must have continued raining on the surface. I left all my warm layers—a fleece layer and balaclava—on while exiting, as I was soaked and never truly warmed up even while ascending rope. Back at camp, I tried to dry off my cave clothes with my body heat by continuing to wear them, but this just made me even colder without drying them out much. It was raining and the air was fully humid. I shivered under the kitchen tarp while I ate my dinner then retreated to bed at 12:40 am. I slept in my wet cave clothes (fleece layers minus cave suit), hoping that a whole night would be enough to dry them out.

Thursday, July 11

The next morning, all that water from my cave clothes had migrated to my down puffy and quilt. At least the clothes next to my skin were dry, so I was reasonably warm and comfortable during the night. Unfortunately, my down layers would be much harder to dry out—not exactly ideal gear to bring on a long backcountry trip in a cold Alaskan rainforest, but it was what I had on me, so I would have to make it work. When packing for Alaska, I also had to pack everything I needed for my subsequent caving trip to Tears of the Turtle Cave in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana, as I would be flying straight from Ketchikan AK to Kalispell MT after this. The Bob Marshall Wilderness is very dry and warm this time of year, unlike Prince of Wales Island. I didn't want to bring heavier synthetic insulation into the Bob, and I certainly didn't want to pack 2 sets of insulative gear in my suitcase for Alaska and Tears of the Turtle, so I had to pick one set to bring, and I chose down. Oh well, I would just have to deal with the consequences of my choice to bring down, which lacks any insulative power if it gets wet and is difficult to dry out.

Thankfully we had some intermittent bouts of sunlight that morning, so I (and others who had much wet gear to deal with) spent some time in the morning hanging gear up where it would get sun and drying it out. Christian, Reilly and I were all feeling quite beat up, from our mystery illness and the many hours spent being wet and cold just as much from the caving itself, and we contemplated the idea of taking a rest day and returning with a vengeance on Friday. While we were imagining how nice it would be to spend a while day drying off our feet, sipping hot drinks under the kitchen tarp, and sunbathing for the occasional moment when the sun peeked out from behind the clouds, we got some info that would nix those plans. Anna, one of the US Forest Service employees, got word on the radio that a major storm was heading our way, and that it would be wise to be off the mountain by Friday night. The forest service folks on the radio kept using the term "atmospheric river" to describe the unusually severe rain event they were predicting. Because we had to pack up camp on Friday, we wouldn't be able to cave on Friday beyond possibly a few hours in the morning. So Thursday, today, would be our last full day of caving. We decided to hit the cave hard one last day today and give it a full day of exploration. We would have Friday morning to derig if needed, although we would try to derig today if we could so we would have all day Friday to pack up camp and hike down the mountain.

The others at camped hemmed and hawed for a while about whether they wanted to continue caving+ridgewalking that day, or hike out today, one day before the atmospheric river. None of the other cave leads had gone so well as our Snowhole lead, so the others had spent much time ridgewalking out in the rain all week. They were tired of being out in the rain all day every day and were ready to hike down. Even I was feeling a little beat up from the constant dampness—I was getting some classic feet issues, specifically some small open wounds on my feet that would not heal due to being constantly wet and in fact were getting worse—but I was certainly not about to hike down early given that we had a wide open lead at the bottom of what was now the deepest cave in Alaska calling our name. Amelia considered coming with us that day, but ultimately decided to hike down instead, alongside Anna, Alex Lyles, and Jared. We made sure to get a group picture with all of us before some of us started hiking down

We sure did enjoy our morning on the surface, slowly packing for the day without any particular rush, as it was just before 3 pm when we finally got in to the cave. We got down to the bottom of the cave uneventfully, and I went to work rigging the drop beyond the dig from the previous day. I was quite surprised that I missed the obvious hole horizontally across the top of the standing room with the too-tight bedrock constriction in the floor. A lesson I've learned too many times: don't get tunnel vision only trying to go down deeper in a cave! Looking up and can be fruitful.

Beyond that hole was a tube in the top of a keyhole-shaped canyon coated in mud. I stemmed out across the tube until the crack going down from the tube got to a comfortable width, and set a traverse line out to that point. Getting in the bolts for the traverse line was quite strenuous and time-consuming, as I had to power-stem into the slick slime coating all the walls, reach high up near the ceiling of the keyhole passage to find good rock not coated in slime, all while merely on rope with tons of slack to give myself room to move around and work. Eventually I got in some bolts that anchored the rope for a traverse line out to where it made sense to start rappelling down into the keyhole, and down I went. It was a low-angle fissure pit with a thick layer of mud coating both walls. As I rappelled down, I couldn't help but dislodge chunks of mud with my feet and dangling cave pack. I was worried about chunks of mud hitting me when Christian and Reilly made their way down. I did get one rebelay in partway down the pit that moved the rope a little to the side, but it could only do so much as the bottom of the pit was a small room without much space to get out of the way of falling mud. Oh well.

The pit was about 90 ft deep, and the bottom was a 4 ft by 10 ft room where the stream, that we lost as it went into breakdown at the bottom of the previous put, and that we could hear but not access beyond the mud dig, finally reunited with us. It poured out of the wall shortly before the bottom of the pit, where the rock changed from muddy to clean-washed, and followed the bedrock floor around a corner down a small passage that I reluctantly squirmed into. The passage went only a few body lengths before getting to a too-tight bedrock constriction, with bedrock walls, floor, and ceiling, and the stream continuing in that bedrock floor past the constriction out of sight. There was no air movement at this constriction. This was a hard ending to this passage, unless we wanted to come back with digging implements (we certainly didn't).

While Reilly and Christian were surveying towards me, I scrambled up a breakdown slope on another wall of the pit than where I came down, aiming for an interesting-looking hole in the wall to inspect. I got most of the way there but didn't like the steep loose breakdown guarding the last part of the climb into the hole, so I backed down and retreated to the floor at the bottom of the pit. I was definitely caving in "DNFU mode" at that time—I had heavily internalized that we were very far from any source of help beyond the 9 other cavers on this trip. Even getting their help would take several precious hours, as one would have to exit the cave (~2 hours), possibly wait several hours for people on the other teams to get done with their trips and back to camp, make them pack up supplies for more caving, then bring them back down to the bottom (another hour or 2). All while whomever was hurt was possibly succumbing to hypothermia or complications from whatever injury they got. If anyone needed more help than the handful of cavers on this trip, it would be at least a whole day (possibly 2) for cavers from the continental US and/or Canada to fly to Ketchikan, get to Prince of Wales Island, and hike up to camp then to the cave. There were no other cavers on Prince of Wales island, and certainly the local search and rescue squads would have no idea how to perform a cave rescue. As always in caving, but especially in these extremely remote circumstances, we took extreme care to be safe and self-reliant, and operated under the assumption that help might not arrive in time if anyone got hurt.

So I retreated from the climb up into the hole in the wall on the other side of the pit and yelled at Christian and Reilly, above me on rope, to look at that hole while rappelling down and swing over into it if they could. I also yelled at them to avoid dropping rocks if they could help it. Since there was nothing left for me to do, I started packing up my things to take out of the cave, then did squats to stay warm until they got down to me. Christian confirmed that the hole in the wall of the pit did not look like a good lead at all, then they both made it down to the bottom of the pit. I confirmed that it was now time to leave the cave, as we had no good leads going down, although we certainly had some good infeeder leads going sideways/up. I packed up as much as Christian and Reilly could give me, and bolted to the surface while the others finished up surveying the short horizontal passage at the very bottom of the cave. I had gotten quite cold waiting there, and was glad to be moving and generating lots of body heat caving with 2 packs.

I carried 2 packs out of the cave because Christian agreed to go last and stage-derig the cave as we left. Stage-derigging is partially derigging the ropes from the drops so they get (mostly) protected from damage during the high waters of the wet season, but not fully removing them from the cave. What you do is remove the ropes from all intermediate bolts in all the pits except the top bolts of all the pits, and coil the rope and leave them attached at the top of every pit. That way, they stay out of the way of raging waterfalls that go down the pits and can damage ropes when water levels are especially high, but you don't have to carry them all out of the cave. Even when you're not carrying them out of the cave, stage derigging is still quite a bit of work, and I volunteered to take 2 packs so Christian wouldn't have much to carry while he stage derigged. We also agreed that he should fully derig and carry out the rope from the landing at -328 ft upwards, as the entrance drop gets tons of debris falling into it from the surface and ropes left rigged there for the whole year are especially likely to get damaged.

Ascending up from that last pit was quite the chore, as the low angle of the wall meant the rope got sucked into it and jammed into the slimy mud. Both my ascenders quickly clogged with mud, and I had to manually actuate their cams with every movement up the rope. And push out from the wall before every movement to make space to push my ascenders up the rope without them being pinned against the wall. This significantly slows down the process of ascending rope and makes it take much more effort, but the bright side was it meant I very quickly warmed up and ceased shivering, as I had been while waiting around at the bottom of the cave. I figured that doing all this with 2 packs would be good training for Tears of the Turtle Cave in Montana, where I would go right after Alaska, as that cave is full of horrible mud that makes one's ascenders never work right, and there are always many heavy things to carry, although we usually stuff them in 1 big bag, not 2 medium ones.

I got out of the cave a little after 10 pm. Reilly was right behind me, although we had to wait maybe half an hour before Christian his way out of the cave, after which we declared victory for the week, with everyone out of the cave and a new depth record for Alaska achieved. The depth of Snowhole Cave with the new discoveries is now 911 ft. I carried 450 ft of 11 mm rope (what we used to rig to the landing at -328 ft) down to camp, awkwardly while the loose coil snagged on every tree branch, but feeling too victorious to be bothered by such trivialities. The mystery illness was hitting all 3 of us especially hard around this time, but again we were in too good of a mood to care. Everyone was asleep at camp when we got there, so we would have to wait til the next morning to tell everyone how our day went.

That night, I slept under the kitchen area tarp, instead of under my small tarp shelter. My reasoning was that it wouldn't get in anyone's way, because the next morning we were going to pack up camp and leave, so there would be no disruption from having to leave my camp setup in the kitchen. Plus I thought the larger, taller kitchen tarp would provide more convenience when getting in/out of my sleeping setup, as my personal tarp was small and thus low enough to the ground so that I couldn't stand up and change/pack up under my tarp. It was raining hard now, and I really wanted to be able to stand up around my sleeping setup without getting soaked by the rain. Well, it turned out that the kitchen tarp was totally inadequate to keep my dry while sleeping, as the heavy winds meant the rain would move sideways into the kitchen area and soak my even when I was completely under the tarp. Also, the ground there was waterlogged and muddy, and brown water from the kitchen area floor slowly worked its way onto my ground sheet over the course of the night. My down puffy and quilt were totally soaked at that point and provided very little insulation. I was quite cold that night, which was especially discouraging as I hadn't really warmed up since exiting the cave the night before.

Friday, July 12

The next day it was time to pack up camp and hike down. The "atmospheric river" was supposed to hit some time that evening. A forest service helicopter had hauled up most of the gear we had up at camp, and would haul most of it down, but we had to package everything up and store it properly so it would last the several weeks until the forest service could schedule helicopter time to take everything down. That meant packaging up all the food in dry bags and Darren Drums to seal in the scent away from bears, hanging it up in the best bear hang we could muster (which wasn't great—it would probably stop a bear that had other easy sources of food, but it certainly wouldn't stop a hungry bear), taking down the kitchen structure we had, and deciding what gear we wanted to take with us and hike down the mountain. That ended up being a lot more stuff than we thought. We made the mistake of not leaving any caving gear back down at the road, instead helicoptering everything up to camp, which was a silly mistake because we had to use some of that gear for the caving we were going to do the next week! In addition to all of our wet and muddy cave clothes and backpacking gear, we also hiked down a bunch of the group food, bolt hangers, quicklinks, and drill and batteries that had been helicoptered up there for us. Note for next time: if you're gonna cave somewhere else after the 1st week, don't helicopter all the caving supplies you'll need for the 2nd week up to your 1st week spot, else you'll have to hike them back down!

It was shortly before 2 pm by the time we were all packed up and ready to hike down. My pack was overflowing with heavy things that made the steep, loose, off-trail hike down especially unpleasant. The sickness was hitting me hard at this point, and I felt uncomfortably hot due to what I assumed was some combination of a fever, the exertion of carrying a way-too-heavy bag down uneven terrain, and the intermittent sunlight we were getting while I was dressed to be cold and wet all day. I kept thinking—isn't the atmospheric river supposed to hit us today? Why are we getting intermittent sun? When we got down to the road, we eventually heard that this atmospheric river forecast was for a totally different part of southeast Alaska, and wasn't even supposed to hit Prince of Wales Island at all. Anna got bad information from the forest service folks who simply told everyone southeast Alaska to go inside. So we lost a day of caving. Oh well, by that point we were all very beat up and sick and ready to be done caving for a day or several.

Another thing we determined when we got down to the road was how heavy my bag was. Hannah had a luggage scale with her. My bag turned out to be…wait for it…too heavy for her luggage scale! We had to use a bathroom scale that she keeps in her converted ambulance that is her house. My bag was exactly 90.0 pounds. Way too heavy! Reminds me of my previous post where I pull-tested my home-sewn caving harness and the strength was too high for the testing setup—it broke the steel carabiner connecting the harness to the break-test machine.

After a little bit of socializing at the El Cap Cave cabin with the cave guides, we departed to Christian's house. On the ride back to his house in Thorne Bay the sickness finally hit me real hard, and I got the chills real bad. As soon as I got to his house, I collapsed into the bed in his guest room and didn't feel like getting up for the rest of the day. Reilly took my temperature and it only read 99F, so I probably didn't have a proper fever, but was just feeling especially fatigued after working so hard many days in a row with a minor-to-moderate illness making it a bit worse. I then proceeded to sleep for 14 hours, from 6:30 pm to 8:30 am the next day.

Saturday, July 13

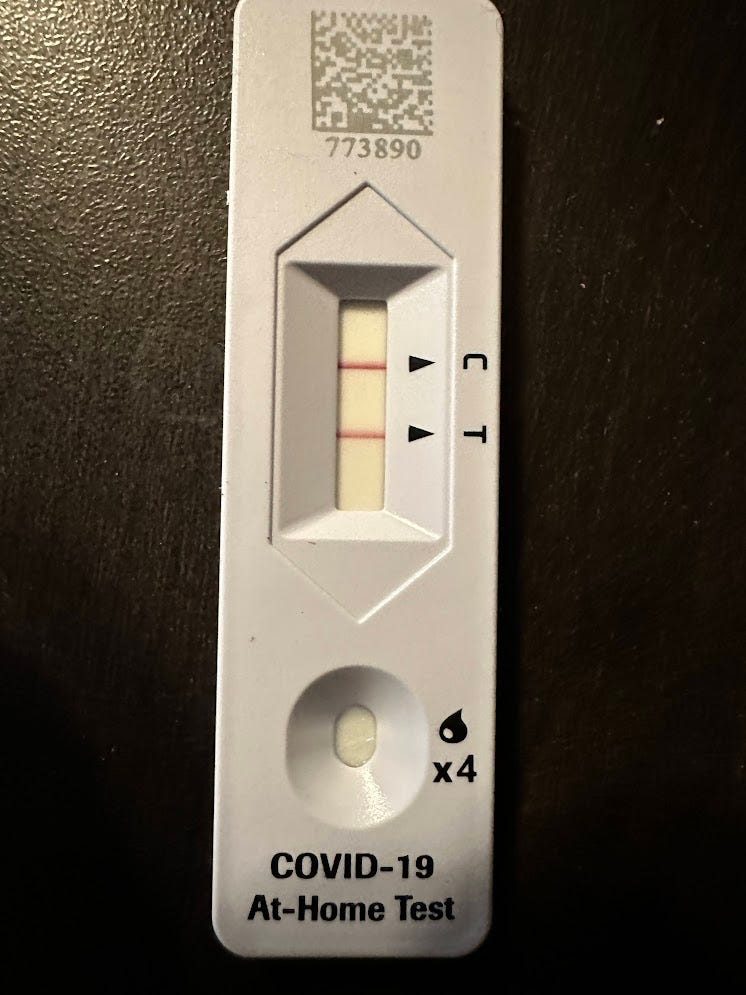

I awoke from my slumber feeling like a new man. Those 14 hours expunged the illness from me real good. Meanwhile, Christian and Reilly started feeling noticeably worse. John had a COVID rapid test on him, and said I could use it if I was curious what I had. I took it, and it turned out that yes I did have COVID, and so did Christian and Reilly too (and Michael, who seemed to have it earlier than all of us and was thus recovered by now). The others who were with us at Christian's house at this point, John and Amelia, didn't bother isolating from us, as we had already spent so much time together at close quarters.

Amelia and John were leaving early the next morning to take the ferry back to Ketchikan then fly home, so they both had to get packing. Reilly, Michael and I were staying another week, so we were in no rush for anything and were in relax, refuel, and COVID-recovery mode. One fun thing we did that day was take Christian's boat out on the water to set crab pots out in the water just outside Thorne Bay. Christian had eagerly told us about the boat he acquired then spent much time and effort fixing up to be water worthy, so we were all excited to see the boat and take it for a spin out on the ocean. We drove down to the Thorne Bay public boat launch, and once we were all in the boat ready to get out onto the water, the engine wouldn't start and kept stalling. Classic old fixer-upper boat problem! After some fiddling with the engine, Christian realized that the issue was a faulty connection on one of the fuel lines, and he got the connection working well and off we went into the bay. We enjoyed the scenic views of the bay surrounded by a heavily forested, uninhabited ridge on one side, and the small, quaint town of Thorne Bay on the other as he brought us out into the middle of the bay where he assured us he had caught crabs before. We loaded the pots with some fish heads then boated back to town.

We got back from boating and Christian made us a nice dinner of split pea and ham soup. It was our first proper meal that wasn't dinner mix since hiking up to basecamp on Monday morning. After dinner, Gooseberry stopped by to bring us some fish he had just caught. He hiked down a day earlier than the rest of us and spent the whole day fishing. He caught a ling cod (unrelated to standard cod) and gave us a nice fillet. After that, we went to nearby Sandy Beach to make a fire and hang out with everyone one last time before Amelia and John had to leave the next morning. When we were there we ran into several of Christian's friends from work at the Forest Service office in Thorne Bay. We chatted with them by the fire for a while. It was quite nice to casually get to know some of the Thorne Bay locals. Thorne Bay is a very different place than Albuquerque, and hanging out with some of the locals gave us a nice little glimpse into what day-to-day life is like in Thorne Bay.

Sunday, July 14

Amelia and John left early that morning for the ferry back to civilization, and it was now just Christian, Reilly, Michael, and me who were sticking around for another week of caving. Because Christian and Reilly felt even worse from their COVID (we assumed that everyone who got sick had COVID, as I had the same symptoms as everyone and tested positive for it), we decided to not get back to caving just yet, and instead spend the day ocean fishing on Christian's boat. Not exactly what I signed up for and was expecting when coming to Alaska, but a fun and welcome activity nonetheless. My feet were feeling pretty bad at that point, as several small open wounds I had on my feet, acquired either before the trip or during, were not healing and in fact had gotten much worse due to being cold and wet all week. Hiking everywhere in my wellies certainly didn't help that problem—next year, I'll definitely bring shoes for hiking around when not in the cave. Given the state of my feet, I was glad to not have to wear wellies nor be on my feet much for a few days while we fished instead of caved.

Us out-of-staters bought single day Alaska fishing licenses, then the 4 of us got in Christian's boat and went out into the ocean again. The boat started up without issue today, and we went to where we left the crab pots to check on them. There was only one small crab in one of the pots, too small to eat, so we let it go and put some more bait in the pots. We then boated our of the bay that Thorne Bay is in and into the wide open ocean. The 4 mile boat ride from Thorne Bay out into the open ocean between Prince of Wales Island and the Cleveland Peninsula on the mainland was beautiful. After we were a little ways out from Thorne Bay, all sign of civilization disappeared, and we were surrounded by steep ridges rising out of the water on both sides of the bay, that were covered in a thick, lush blanket of dark tall pine forests. A few tiny islands dotted the bay and provided minor obstacles to navigate around. Christian even let me drive the boat at one point. One of the tiny islands in the bay, Tolstoi island, had a group of seals hanging out on the rocky shore.

We boated around and tried fishing at several shallow spots near the mouth of the bay. The first thing anyone caught was a hunk of coral that I dragged up from the sea floor. After that, we all started catching tons of rockfish. Rockfish are apparently slightly endangered in this area, and only Alaska residents are allowed to keep them, and only 1 per day at that. We were all somewhat surprised that rockfish are threatened, because we all caught many of them. Maybe they're dumb and easy to catch and that's why they're threatened yet you always seem to catch plenty of them.

After switching fishing spots a few times, we finally found a spot where we caught plenty of fish that we could keep. Once we made it to this spot, Reilly, Michael and I started catching Pacific cod every few minutes. We caught 6 cod in the remainder of the afternoon and kept all of them as they were all a pretty good size. My total for the day was 3 cod, 3 rockfish (none of which I could keep), and one pretty hunk of coral. One of the cod I caught freed itself from the hook at the last second just as I was about to reel it into the boat, but I was able to grab it and snatch it out of the water before it could swim away. Probably it was in too much shock to swim away after being hooked and dragged up from the sea floor. I was particularly proud of that catch and definitely wanted to keep and eat that one.

One of the coolest sights we were treated to while catching cod at this spot was several bald eagles circling us, clearly looking to capture any of the fish we were bringing to the surface that they could probably smell and see. Once when we caught a rockfish and threw it back, the fish was stunned (or dead?) and hung out on the surface for a bit. A bald eagle saw it and swooped in trying to capture it. But it missed! We were surprised it missed given that the rockfish was sitting in the water immobile.The whole thing was a classic Alaska sight. Michael even got the whole thing on video. After the eagle left, the fish continued drifting out of sight on the surface of the water. I hope it came to and made it.

Once we got home with our haul of 6 cod, it was time to gut and fillet them. Christian knew how to do this of course, but figured it would be a fun learning experience to leave us to our own devices to figure it out on our own. I had done this once a few years ago with trout, but cod are anatomically different, and I didn't even remember how to gut trout anyways. Reilly and I pulled up a YouTube video and got to work while Michael watched—he could tell that we were both very eager to learn and practice this new skill, while he was pretty neutral about it, so he let us handle it. We watched the YouTube video a few times and figured it out without a hitch. Honestly, the hardest part was touching our phone to rewind the video while our hands were covered in fish guts. After we got all 6 cod gutted and filleted, we froze some of them and used the rest to cook a delicious dinner of cod and rice. Now we were finally eating like kings and queens! No more dinner mix for now.

Monday, July 15

The next day Christian and Reilly still felt pretty bad with COVID, so it was not yet time to go caving. More fishing! Instead of going out on the ocean and fishing for cod (with the chance to catch Halibut), today was a day to fish at a river and get some Salmon. Reilly's COVID was worse than the day before, so she decided to stay home and rest. Christian, Michael and I went to hatchery creek, which is set aside by the state for subsistence-only fishing. Christian has a rural subsistence fishing license, so he was allowed to fish there, and he was allowed to fish via dip netting, which is using a large handled net to scoop fish out of the water. Dip netting is much more effective than fishing with a rod in terrain like Hatchery Creek, where salmon running upstream are funneled into a few narrow areas where you can clearly see them and scoop them out of the water. The sockeye salmon were running at this time, and went we got to the creek I could immediately tell that this would be a good location and time to catch salmon as I saw multiple jumping out of the water.

This specific spot at Hatchery Creek has several short waterfalls that the salmon jump up as they swim upstream looking for a spot to mate. I didn't know that salmon could jump so high out of the water! It was quite impressive seeing them launch 6+ ft into the air, stick the landing into the top of the waterfall, and continue swimming upstream as soon as they were back in the water. Such gymnastic feats were nice to watch, but also useful as they provided a dip netting fisherman a signal that a salmon is coming their way. Just upstream of the little waterfalls here were narrow channels that the salmon get funneled into, so right when you see one jump you know to keep your eye on the channel and scoop with your net when you see a salmon swim through. Christian caught 6 sockeye salmon in about 2 hours using this method.

Michael and I were not allowed to fish via dip netting, as that method is for subsistence use only in Alaska, so we entertained ourselves by watching the salmon jump, watching Christian scoop them out of the water, and wandering around picking blueberries and salmonberries to eat. Both blueberries and salmonberries (like blackberries, but with a rich yellow or red color) were abundant here and now. The abundant berries and salmon made me think this is perfect bear habitat, and I'm sure that bears would perpetually hang out at this spot if humans didn't frequent it. In fact, we ran into 2 locals who were hunting bear there, and chatted with them for a while. They live in Coffman Cove, an even smaller, more isolated community than Thorne Bay on Prince of Wales Island.

Once we got back to Christian's house with another haul of 6 gorgeous fish, it was again time to gut and fillet them. Salmon are slightly anatomically different than cod, but the skills transferred and I gutted and filleted 5 salmon after Christian showed me how to do it using 1 of the 6. At Reilly's request, I also saved the roe (eggs) from the female salmon, as apparently it is a delicacy. Like the day before, we froze a bunch of the fish and kept some out to cook a delicious dinner.

Reilly prepared the roe with a half hour salt cure. I tried some when it was done curing and was a little put off by the intensely salty brine that gets released into your mouth when you chew and pop the eggs. The eggs have a fairly mild fish flavor, but the salt was a bit much for me. I figured they would be excellent to eat with rice to dilute the flavor a bit, rather than straight up. I cooked up 2 fillets from 1 fish for everyone, and we ate it with rice and roe. The roe was indeed excellent eaten with rice; it seasoned the rice and gave it a wonderful yet mild fishy flavor and aroma. I'm glad she made me save it from the salmon, as I wouldn't have thought to eat it, but now I know how delicious it is. Now we were eating salmon fillets and caviar, way more luxurious than dinner mix!

After dinner, I started a repairs to address some gear damage from the previous week. I needed my gear to last through some caving this week, but also the next 2 weeks at Tears of the Turtle Cave in Montana, a harsh, difficult cave notorious for destroying gear, among other things. I used some Shoo Goo to glue together the foam at my helmet where it cracked, and I started extending the homemade pocket for kneepad foam in my cave suit to make it better cover my knees. Again I was glad that I brought my speedy stitcher. I cut up some fabric form my rain pants, which were full of holes and not worth keeping at this point, to extend the internal pockets. I also extended the foam itself my cutting up my flip flops and attaching their foam sole to my kneepad foam with the speedy stitcher and some Gorilla Tape. We were planning on finally caving again the next day, so I needed to have functioning cave gear by the morning.

Tuesday, July 16

Today it was finally time to cave again (not that I minded the previous 2 days of fishing and, more importantly, eating lots of fish). I finished up my kneepad modifications in the morning before everyone else was up, and started packing for a day of caving. Reilly was still having pretty bad COVID symptoms so she decided to stay home again. Christian, Michael and I would be a team of 3. We would be recreating the Fast and Heavy team, as we called ourselves, from the previous year.

We had a lead in mind in Zina Cave in the Staney Creek area, which is a flatter, low-elevation karst area with more horizontal than vertical passage about an hour from Thorne Bay. Local caving legends Kevin and Carlene Allred explored Zina in the 2000s before moving away. Zina is a little over a mile of mostly horizontal passage, with some short vertical drops in a mazy area near the entrance that guards the large, walking stream passage that forms the main trunk of the cave. There was one lead left on the map marked "continues large and horizontal", that seemed like an infeeder to the large and horizontal trunk passage. It sure sounded promising!

We were on a fairly late lazy schedule and didn't get into the cave until 3 pm. The entrance is a pit in a large sinkhole that leads into an interesting and confusing mazy area full of walking and crawling tubes going in various different directions. Christian had been to the trunk passage before, so he navigated us through the confusing tubes to the drop into the trunk passage. This drop is a small hole in the floor of a walking tube that one could easily overlook if there weren't a rope bolted to the wall going down into the hole. This drop had several tiers with ledges between them, and there was bad rope rub on some of them that Christian wanted to fix, so he went first and took the drill to put rebelays in the drop and make it freehanging. After he announced that the drop was rigged properly for all of us, Michael and I followed him down to the water. I was eager to get moving at that point, as I had gotten pretty cold waiting for Christian to rig. Now I was getting a taste of my own medicine, waiting around in the cold and shivering while someone else went ahead and took a ton of time rigging.

At the bottom of the drop, we scrambled down to the floor of a tall walking canyon with a stream in it. The rock was polished and hard, and it seemed marble-like, although this could have been just due to fast-flowing water polishing the rock rather than metamorphosis of limestone into marble. We walked down this canyon as it slowly transitioned from narrow sideways-walking to spacious borehole. There was one tricky section where we had to find a way to downclimb a ~15 ft waterfall drop. And we did expend some effort tiptoeing around the spots with the deepest water, and stemming high above the water, to avoid flooding our wellies and getting our feet wet. Other than that, the travel to the lead was straightforward once we were in the trunk passage. It appeared as an obvious large passage on the right, above the stream level in one of the largest, most impressive sections of the trunk passage.

We went a bit down the passage to see what it did before getting into survey mode, and found that…the passage immediately died. Bummer. It turned into a too-tight wet crawl. We surveyed a few shots from the nearest station to the end of the passage, just to get something on the map, and got 60 ft of survey. Can't win 'em all.